AI will change how you consume result sets (and that's good)

I'm using Claude to get "evidence-aware" search results, and I don't want to go back.

A defense of the humble result set

I think when LLMs first came out the assumption was that the main impact on search would be replacing result sets with answers. And that’s been a lot of the shift, and there’s pros and cons to that.

Sometimes a straight-up answer is what you need. I don’t need a portfolio of sources when I want to know what weight oil my car takes, or who founded the city of Eugene, Oregon. (Was it named after the founder’s first name I wondered? Yes it was. It really was named after a guy named Eugene.)

But when it comes to research, result sets are invaluable. And augmenting research — not providing answers — is at the heart of knowledge expansion. Result sets, as I’ve argued with my co-author Sam Wineburg, help us to read the room on a subject — seeing what various sources are contributing to a discourse, and giving us a sense of what’s settled, what’s debated, and how those debates break down. Reading a result set gives a view of a subject that resists easy summary, and prepares us to enter the conversation ourselves. Even when questions are fairly simple, result sets resist the tendency of AI answers to puree sources and insights into an AI information smoothie, a response which goes down easy but disguises its underlying ingredients and contradictions (yeah, I’m pushing this metaphor, live with it) in ways that aren’t always helpful.

So, just because we can get AI answers doesn’t mean we should abandon result sets. To do so would treat human knowledge as a finite pool, rather than a foundation to build on, rather than pieces to rearrange. We won’t need it for as many things as we used to, but we’ll definitely need it.

Recently I’ve been thinking of some possible ways that LLMs can enhance result sets, in particular through being “evidence-aware”. And I’m starting to think there’s a lot of future left to be had in AI-augmented traditional search, should we want to pursue it.

And in case I’ve not been clear, we definitely should pursue it.

From result set to sources table

The SIFT Toolbox I built has an output I designed called a sources table. I think it shows a hint of what search in the future will be like.

What do I mean by that?

A good example came up today when I wondered where Trump had gotten a claim — one he first made in 2018 but apparently rehashed recently. The claim was that Japanese regulators dropped bowling balls onto imported American cars as part of a safety test designed to cause them to fail.

So two things. First, this isn’t true. Japanese regulators don’t do that. Second, Trump probably just misheard something in conversation 20 years ago and it became a core belief as he repeated the story over time. Occam’s razor there.

But a good searcher doesn’t simply go on instinct. The “F” in SIFT requires that we see what other people have said about this before we lock into our own conclusions. And so we turn to search to do that.

Traditional search

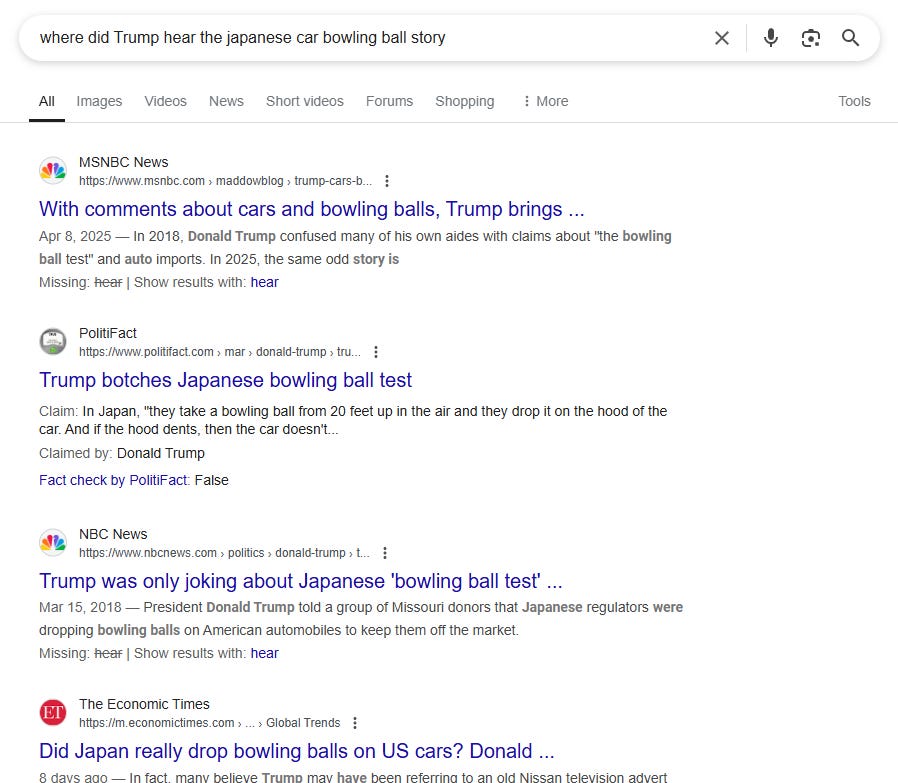

The way I’d normally do this in search for something like this — my query below is a bit wordy, but you get the point. I search for something like origin bowling ball story or where did trump hear bowling ball story. (I know the stop words don’t get counted but I tend to throw them in anyway for good reasons I can explain later if you want, just ask me in the comments).

So you do that search and… you get a great set of resources actually. It’s really good!

But look at how it is ordered below and get the feel of what it’s like to skim this trying to learn more about specific theories about where this bowling ball story came from:

Each of these probably has information about where Trump might have gotten that story, and normally the procedure is to go into each one, skim or search to see what possible origins it might mention, then go to the next result. Click in, skim, go back. Click in, skim, go back.

This process has some things to recommend it — for one, the need for users to click through each link to see if the page provides insight is better aligned with ad revenue models. So I want to raise that issue as something outside the scope of this post, but a larger issue.

From a user experience perspective, though, it’s a clunky search result and a horrible process. The searcher is already aware of some theories but not others, but there’s no way to get a snippet that indicates what theories each page has. So what the user has to do is click through multiple links and see if what they see there is the same story as the last one they clicked or if it’s something different.

Sources Table in SIFT Toolbox

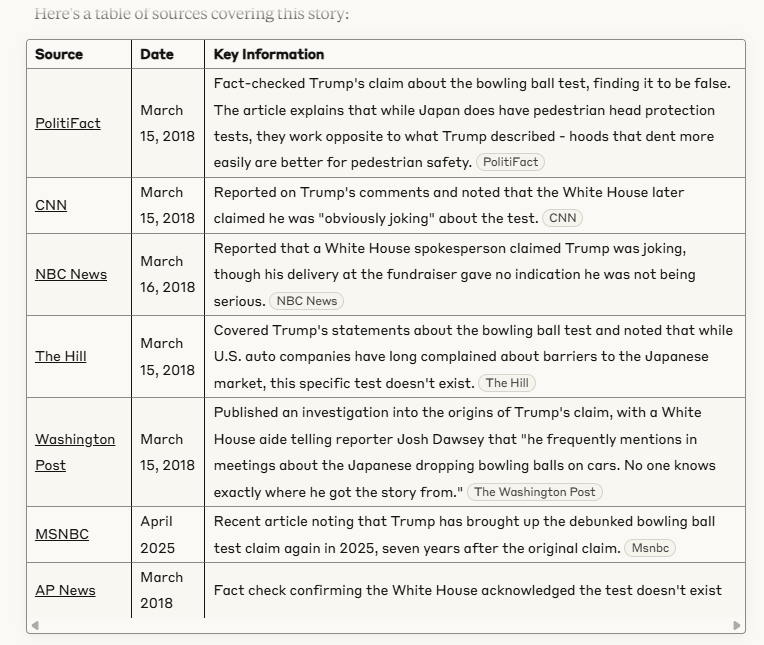

If you just go into Claude with no larger instructions active and tell it to make a table of links you already get something that is more useful, providing a summary that links to your question directly:

But as you skim through this that you realize you have the same problem as the search results. As a researcher, what you want to make sure that you know all the theories out there, and make sure that for each theory out there you have at least one page you can click through to see more information (and perhaps use as a citation). Your unit of research is not really pages — it’s underlying facts, claims, and theories. It’s the stuff you have to collect, check, and integrate as you build your understanding, not the pages themselves.

That’s what SIFT Toolbox’s “sources table” is about. So, for example, I start a session by uploading this text:

And if once the system runs the initial analysis on it I type:

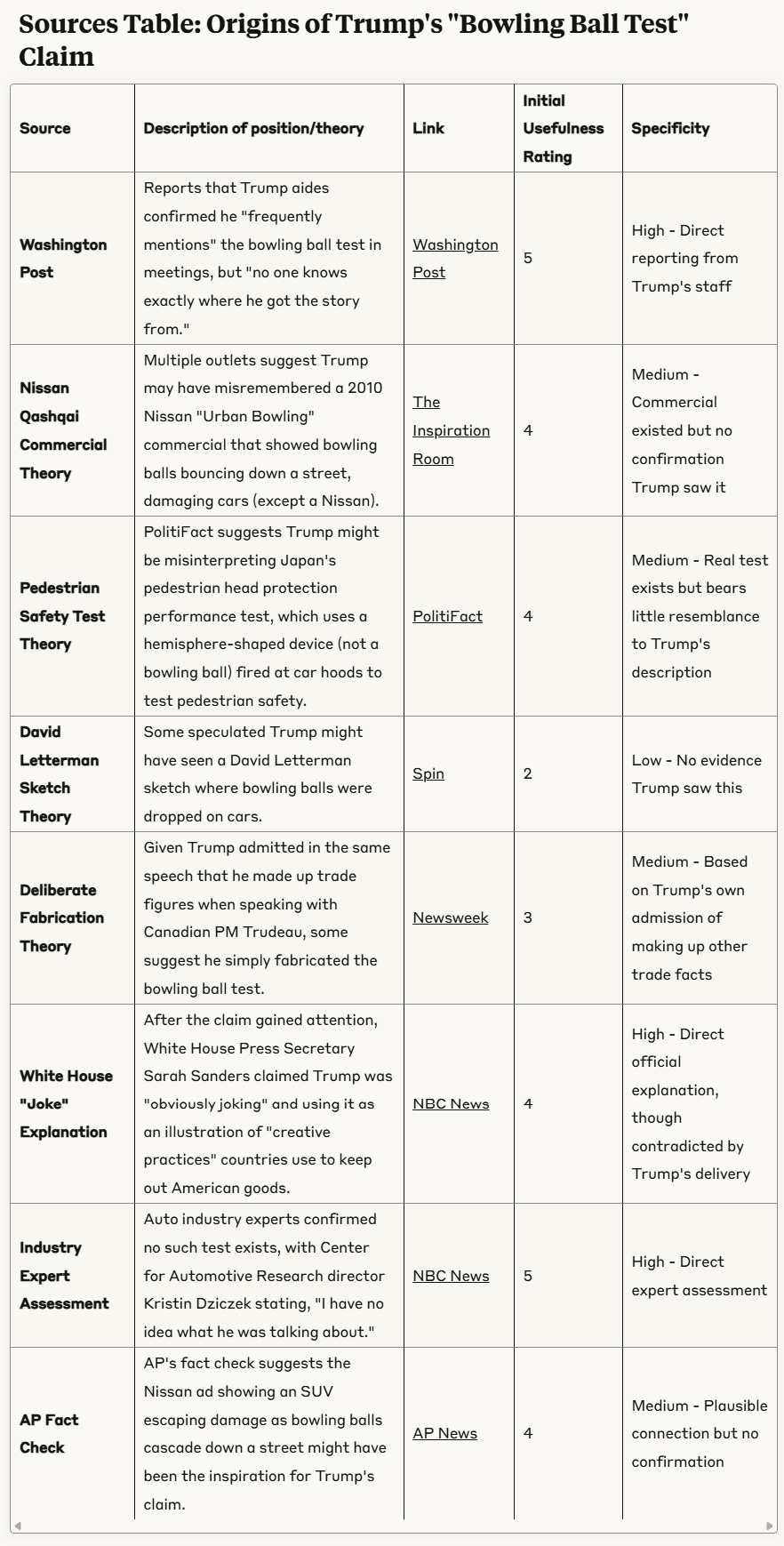

That will produce this:

Now, note the difference here — this search response is still a set of results, but is not organized solely as a set of sources. It’s organized by your investigative needs. By the pieces you need to explore what linguists call the QUD — the question or questions under discussion.

You have a list of the different known explanations for Trump believing this story, and for each one you have a summary of what piece of evidence regarding that that the page brings to the table. Obviously, many pages cover multiple theories, but with this design I know if I want to know more about the David Letterman claim I can go to the Spin magazine links, and if I need any industry reaction I can click through to NBC News. You’re looking at sources, but they are organized according to the needs of the sense-making task you are engaged in.

For this Trump example the table was formed around the different theories about the bowling ball, but in other cases the sources table forms around different elements of a story, and describe what unique element the source brings to that story/context.

For instance, there is a test I do that uses this screenshot as an input, a snapshot of a video from the 1972 Olympics gymnastics competition and a description that reads:

“The banned ‘Dead Loop’ of Olga Korbut in the 1972 Olympics. It was the first and last time the trick was performed.”

Ominous!

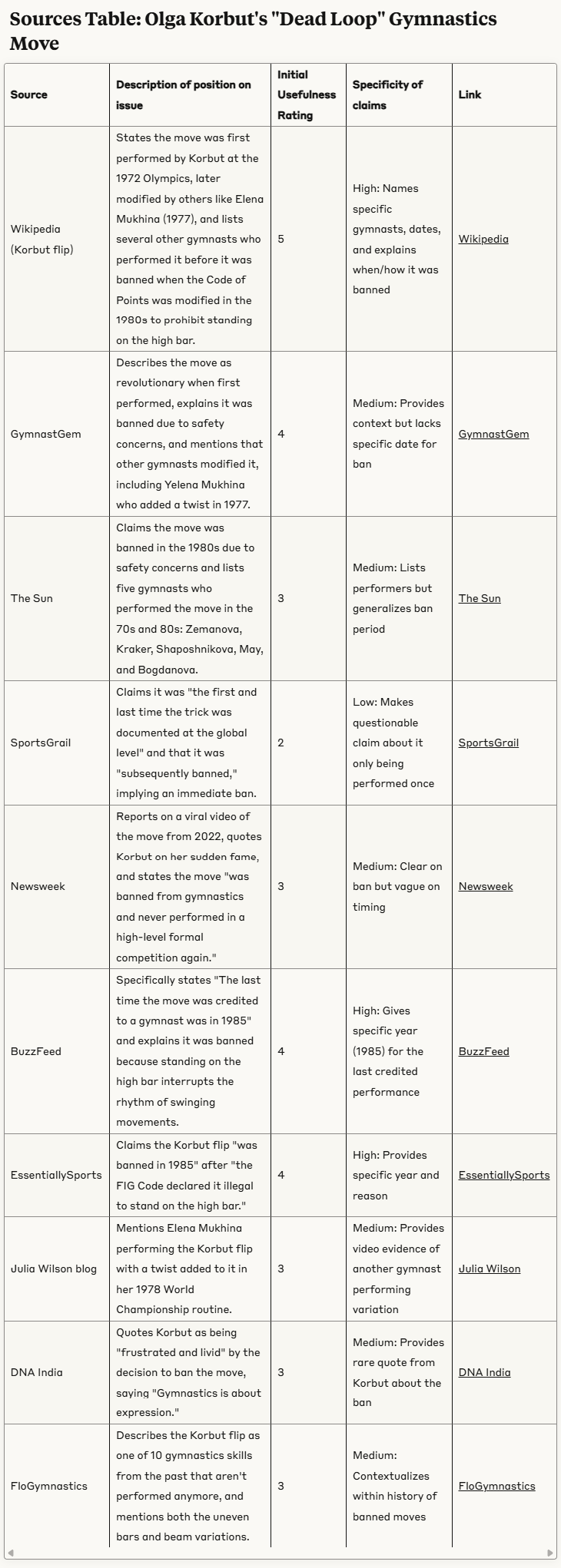

Now this isn’t true, as the automatic fact-check SIFT Toolbox will tell you. Variations of this move were used up until 1985. It was banned for safety (mostly) but it wasn’t as movie-level dramatic as this makes it out to be.

If you ask for a sources table here, SIFT Toolbox shows what each source might bring to the larger context you are constructing. For instance, the result set shows that Wikipedia can give you the overview. That Gymnast Gem confirms how revolutionary the move was, and mentions another gymnast added a twist to it in 1977. That The Sun, which is not a great paper but probably OK here, gives the names of five other gymnasts said to have done it after her. That Buzzfeed provides a specific date (1985) when it was last done and DNA India seems to be the one source that has Korbut’s more recent comments on what she thought of the ban. And that FloGymnastics lists nine other moves that were either banned or fell into disfavor, providing some larger context.

This is a quiet revolution in search, actually

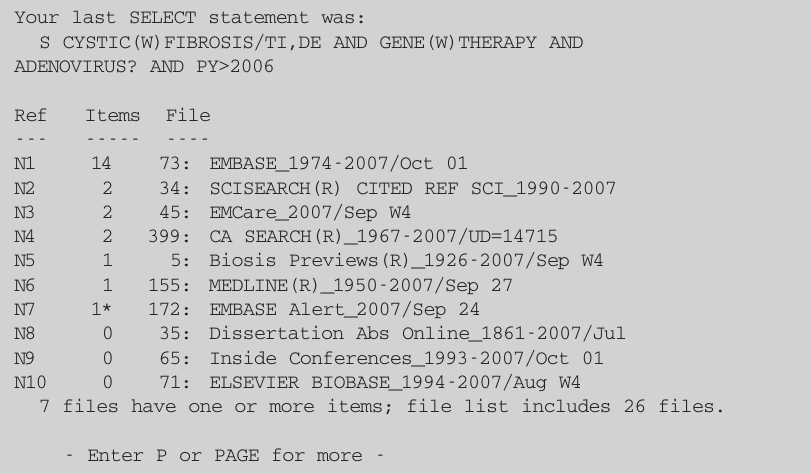

I’ve been searching documents since the days of command-line Dialog (I couldn’t find a Dialog screenshot from 1992 so I grabbed this 2007 one instead).

Search has gotten a lot better over the years, and the improvements are too many to name. But I think this ability to structure and preview result sets in this evidence-aware way is one of the biggest shifts since full text search.

Part of the reason I know it’s a big shift is that I’ve become a bit addicted to searching this way, using the SIFT Toolbox sources table. I am, after all, a person who loves traditional search, who made teaching traditional search my life, who along with Sam Wineburg wrote one of the definitive books on using traditional search for sense-making. I am not joking when I say that a search curriculum I co-designed has been offered to over a million people around the world.

And yet I find myself making this my first stop more and more.

As you can probably tell from this post, I still lack a language to talk about this, jumping between evidence-aware, claims-aware, sense-making, investigative needs and smoothie analogies. I hope I’ve gestured clearly enough in the direction of my thinking that you, the reader, can see something of what I’m seeing here. If not, I’ll be coming back to this issue in a future post, when my ideas are a bit more settled.

P. S. if you want to try the sources table feature, there’s instructions for using the Toolbox here. I recommend that you use the $20 version of Claude and run the toolbox under Sonnet 3.7.

Reminds me of clustering search results (which never quite worked well enough…).

I’m not really sure what to do though- maybe it could better than before since presumably query understanding works better now? Or maybe a contextualization paragraph could explain to user how the groupings were done?