Google Search's AI is (or should be) about cognitive load

Web search has always existed as a weird bargain. People write documents for one reason. Maybe they are writing a news story, or promoting their plumbing business. Maybe they are a company putting out a whitepaper, or a research hospital posting an FAQ on plantar fasciitis as part of public outreach. A lot of time these people are selling something, because writing, research, and expertise costs money. These people writing for status or money create a dense network of information on the web answering a set of questions that earn them status or money.

In comes the web searcher, a person who, quite often, asks a question to which there is no inherent status or money attached. They want to know if a better sneaker can help their plantar fasciitis. They are interested in what the film was where Nicholas Cage had the diapers and the baby. They may wonder for their job whether students do better in classes where they have recorded videos of classes – or worse.

This may seem a simple point to make, but no one is paid to answer their questions specifically. Search is often seen as a marketplace, but it’s more like a rummage sale. Your chance of finding an item that addresses your specific issue, and just your specific issue, is pretty low. You’re not walking into a custom tailor. You’re in the thrift shop, going through suits made for or bought by someone else, seeing if you can put something together. Some assembly may be required.

What do I mean by this? You want to know if a sneaker can help your plantar fasciitis, and if so what its features should be. What sorts of pages are there? There are pages from sneaker companies who say, unsurprisingly, yes. There are pages on plantar fasciitis (great!) which somewhere in the 17th paragraph might mention something about sneakers. There’s a magazine article about the best shoes for plantar fasciitis – which gets a bit ahead of our question, but might be a place to start. There are more pages from sneaker companies. There’s a Reddit group on plantar fasciitis which has a post that says that shoes won’t cure your plantar fasciitis. The heading for that (somewhat confusingly) is “Which shoes cure your plantar fasciitis?” There’s a research paper (in English) from a Lithuanian medical journal that details the impact of a recent controlled study testing the effects of therapeutic insoles on the condition in a group of women. In between this you do see the occasional youtube that gets close to answering your direct question – from someone you’ve never heard of before.

It’s a lot.

Early visions of a knowledge web imagined a different world. Paul Otlet’s Mundaneum at the beginning of the twentieth century imagined cataloging all the world’s knowledge in cross-referenced and tagged index cards. Somewhere in that stack, accessible through “radio telescopes” – would be a card on afflictions>plantar fasciitis>efficacy of better shoes.

But Otlet’s world never had a business model, not even in the days where he could hire intelligent women with few other opportunities on the cheap to do his logging and indexing of information. His dream of breaking the world’s information free from the tyranny of the book missed that there is a paying clientele for books and articles, often formed around some contested question. There is not a paying market for summary paragraphs.

And so we ended up here, in the global information thrift shop, most often trying to piece together an answer to a question out of the paid work of others, paid to do something different than answer our question, for people other than us.

And here’s the unspoken truth about that thrift shop. Using it to get an answer to our question is mentally taxing. I know this because for over a decade I watched students navigate Google results. You’ve got a wall of results in front of you, and almost invariably the ones that address your question directly are the lowest quality ones or the ones trying to sell you something. The ones that have real heft to them always seem to be a bit to the side of your question. For a long time in search, the best practice was not to ask your question (nobody reputable was answering it) but to think of the topic of a larger piece that might answer your question (not “can better shoes cure…” – too optimistic! – but rather “shoes plantar fasciitis”). Once you chose your preferred source of information, an adept user of the web would click through to the page and use control-F to get to the “shoes” bit. But most wouldn’t, because they don’t know how to search in a document. So they’d skim the document (skimming also adds cognitive load) hoping they’d see an answer to their question, and not finding it, or in some cases literally just start reading.

It’s sad we don’t teach this stuff. My years of practice and research show that mastering traditional search is teachable, across all ages and demographics, and often with very little investment of time. Those who learn better searching – how to read the “search result page vibe”, how to select sources that match their needs by using “about this result” features, and yes, even how to ctrl-f your way to the important bits – unlock one of the most important personal and professional skills they can acquire. That’s why I wrote a book about it with Sam Wineburg. SIFT, the methodology at the core of that book, is the result of thinking intensely about the cognitive load of online information-seeking. Underneath the seemingly simple steps of SIFT is a fast and frugal tree model which minimizes such cognitive load by serializing decisions to reduce the amount of material an individual engaged in evaluating information must hold in their head at one time. Source is good enough for your purpose? Great, you’re on your way. Not what you need? Chuck it, forget about it, execute a better search. That serialized approach is one reason why the method outperforms the “checklist” approaches that preceded it. It worked in part because we understood and addressed the cognitive load of fishing through that global information thrift shop. And once you learn an approach like that, you can navigate that environment with ease.

We could have taught this at scale, had we chosen to, but as a society, for reasons somewhat opaque to me, we chose not to. It’s eight years after this country supposedly started to take navigating online information seriously as a core social concern, and we’re still teaching search in library session one-offs, often using outdated and sometimes harmful methodologies. (I don’t mean to minimize the work that many have done here, including my work with Google back when I was at the Center for an Informed Public. We’ve reached a ton of people, it’s done a ton of good, but it’s still a fraction of people searching.)

And so we’re left with the experience of the untutored user. They’ve never been taught to read the “search result page vibe”, they can’t ctrl-f or use find on their phone. They ask a question to Google and from their perspective get a list of things none of which quite fit. That effort has been made better over the years with snippets, and direct paragraph level links into the documents, but it’s still on overwhelming level of cognitive integration and synthesis for the untutored.

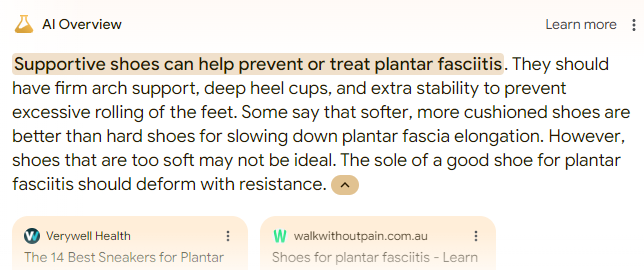

So what is AI doing for them? It’s giving them those parts that we taught students to integrate. In our book, we teach students to read the “search result page vibe” as a first step in search – given the set of results you got, what does it tell you about the topic, and what does it tell you about your search. To some extent, that is what the AI results can be seen as doing – when they work:

That is, the charitable interpretation here is that for a user who has trouble skimming search page and reading the vibe, this is giving them the vibe. And they could use that to ground the rest of their investigation. This summary is, in fact, the sort of thing we’d want people to get from reading a SERP vibe. It summarizes the overall consensus the collection of results represents. It surfaces important terms we might not be aware of – heel cups, rolling of feet.

It’s possibly – and I am still somewhat ambivalent about this – a good replacement for a step in getting an answer. But here’s my issue. It’s not a good answer.

First of all, it’s an answer from nowhere. I mentioned that there were a lot of shoe companies on that result page. Is this answer formed from information provided by the Mayo Clinic or from New Balance? With the blender of AI set on the puree setting, we’re never quite sure.

Second, that “hard vs. soft” summary is confusing at best. A better answer (as far as I can tell from my own research) is you want a hard elevated sole, but with a cushioned heel. The deform with resistance part is confusing and not explained in any way that makes sense to me.

Finally, when I don’t synthesize myself, I miss important things I learn while synthesizing. Doing this search myself, I keep seeing an important piece of advice on plantar fasciitis – wear your shoes in the house, wear them every time your foot hits the ground. That was not part of my initial question, but it turns out to be one of the more important things I’ll learn. A good read of the search page gestalt (our fancier word for vibe) would let me know this – usage patterns are just as important as shoe choice in this case.

So it’s a lousy answer. But I think I start to see a possible direction here as a step. It does let me know that I’m not crazy, shoes really might help. It does give me the set of terms – heel cups, arch support, stability – that I’ll want to keep an eye out for. In some ways it mimics what I would want a student to take away from a scan of the search results. My worry, of course, is that it – well, it looks like an answer. And while that’s maybe OK here in limited ways, in cases where the summary is telling you to drink your own urine, it’s less ideal.

Anyway, I am still ambivalent about this all. But my current thinking is the more we think of this as bundling up a current step of search that most people skip because they either don’t know how to do it or find it too cognitively taxing, the better. I see elements of that in the current design, but I’d really like to see this functionality better theorized in that way.

When ChatGPT first came on the scene I was thinking it could be used to create "stepping stone" sources for students to use in the early stages of the research process. But I share your concern that things that look like answers are much more likely to be used as an end point rather than a starting point.

I wonder if you've seen any writing about the sources being linked in Google's AI summaries. I keep encountering poe.com (Quoara's AI chatbot) in the linked sources, which seems... extremely bad. I wrote my own post about it here: https://necessarynuance.beehiiv.com/p/need-talk-google-722e

If a LLM had information retrieval and synthesis as its core functionality, this would make sense. But LLMs aren't like that at all -- they simulate discourse. To the extent that they look like they're synthesizing information, that's because their training set and add-on doodads have discourse enough like the answer that the billions of parameters make a synthesis-looking chunk of text possible. But it's all text extrusion. No knowledge.

And what that means is that an AI answer to search queries can *add* cognitive load, because you have to sift for the bullshitting.