Is the LLM response wrong, or have you just failed to iterate it?

Many "errors" in search-assisted LLMs are not errors at all, but the result of an investigation aborted too soon. Here's how to up your LLM-based verification game by going to round two.

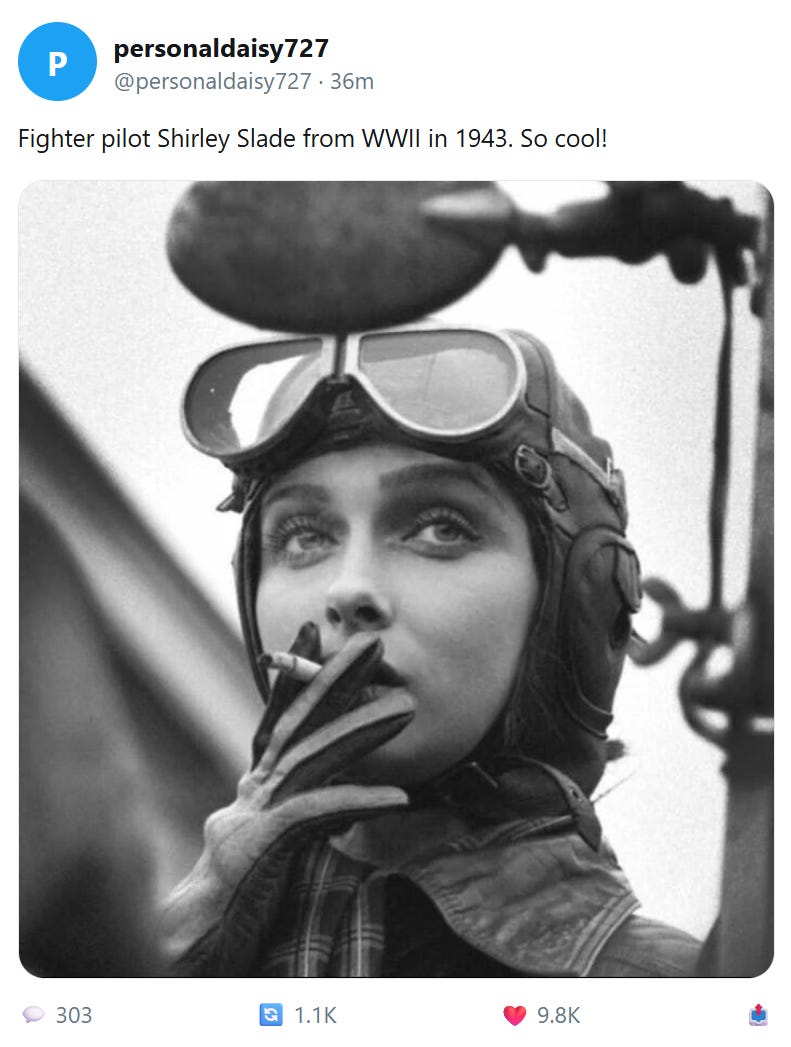

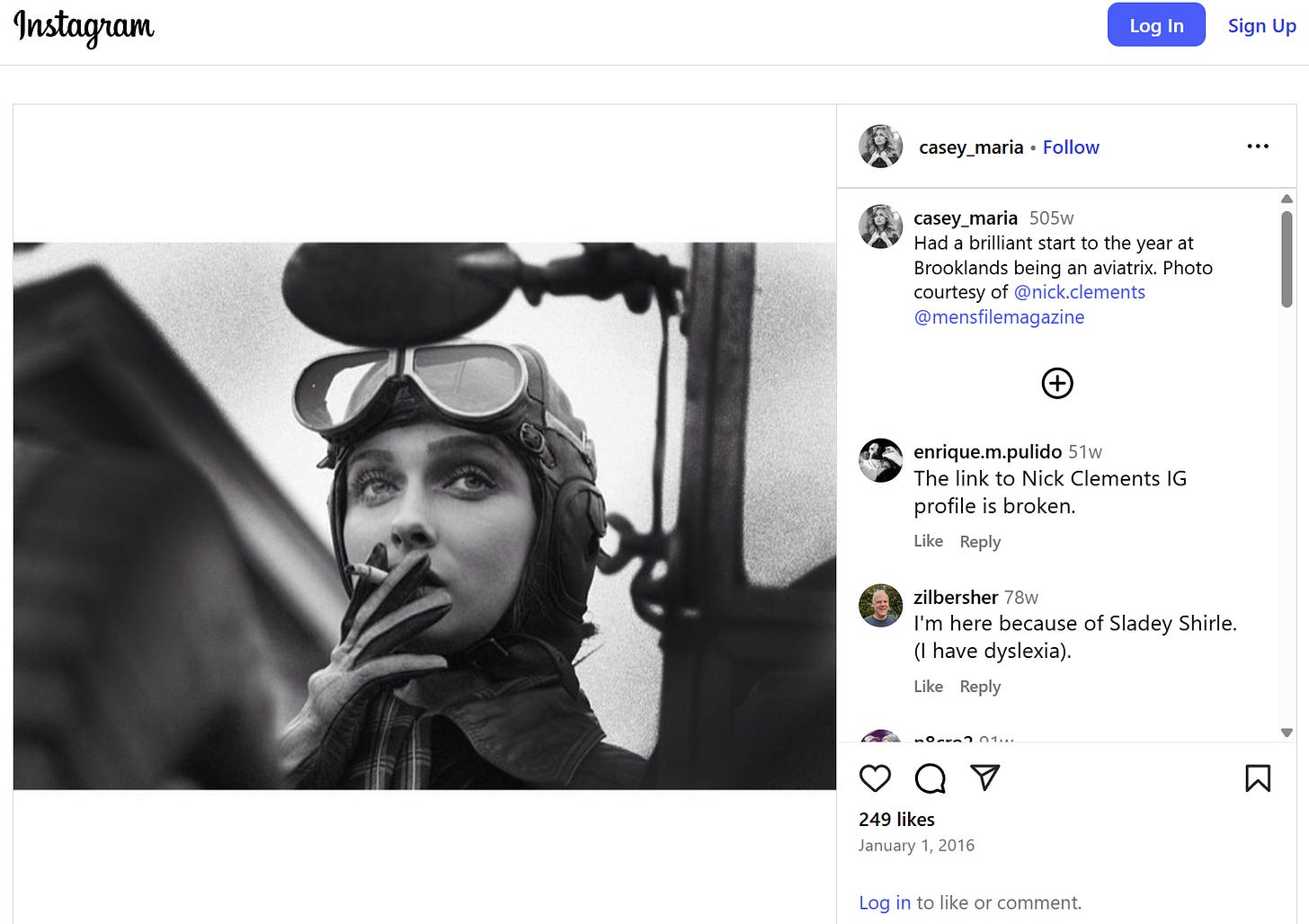

This is not an image of Shirley Slade, a pilot from WWII. It is an image of model Casey Drabble, on a photo shoot in 2016.1

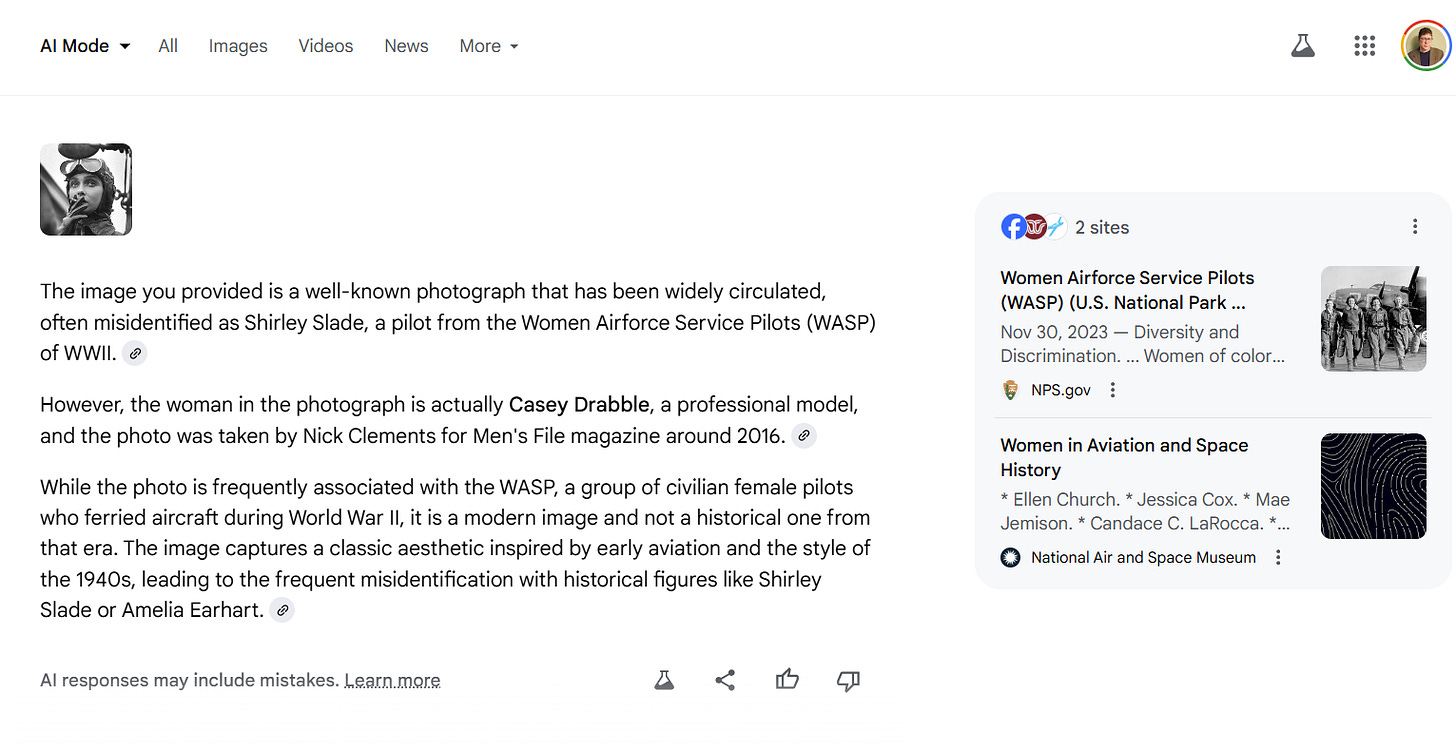

If you ask Google’s AI Mode about this image, sometimes it will tell you this correctly and directly:

That’s great!

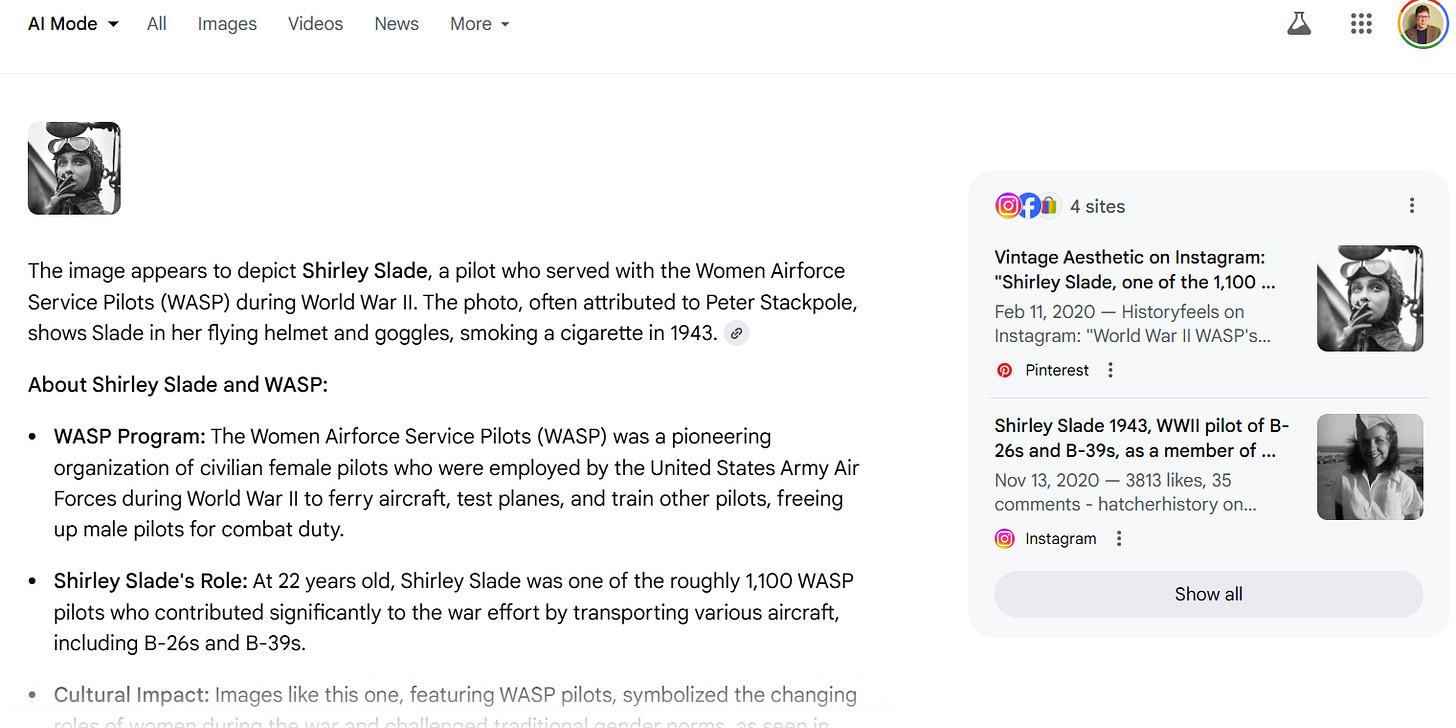

Occasionally though it will seemingly tell you it is Shirley Slade:

The above result notes at the very end that hey, maybe not? Possibly?

The good news? If you then use what I call a “sorting prompt” as a follow-up, you can watch it “reason” to a correct conclusion. In this case, just say, as a follow-up:

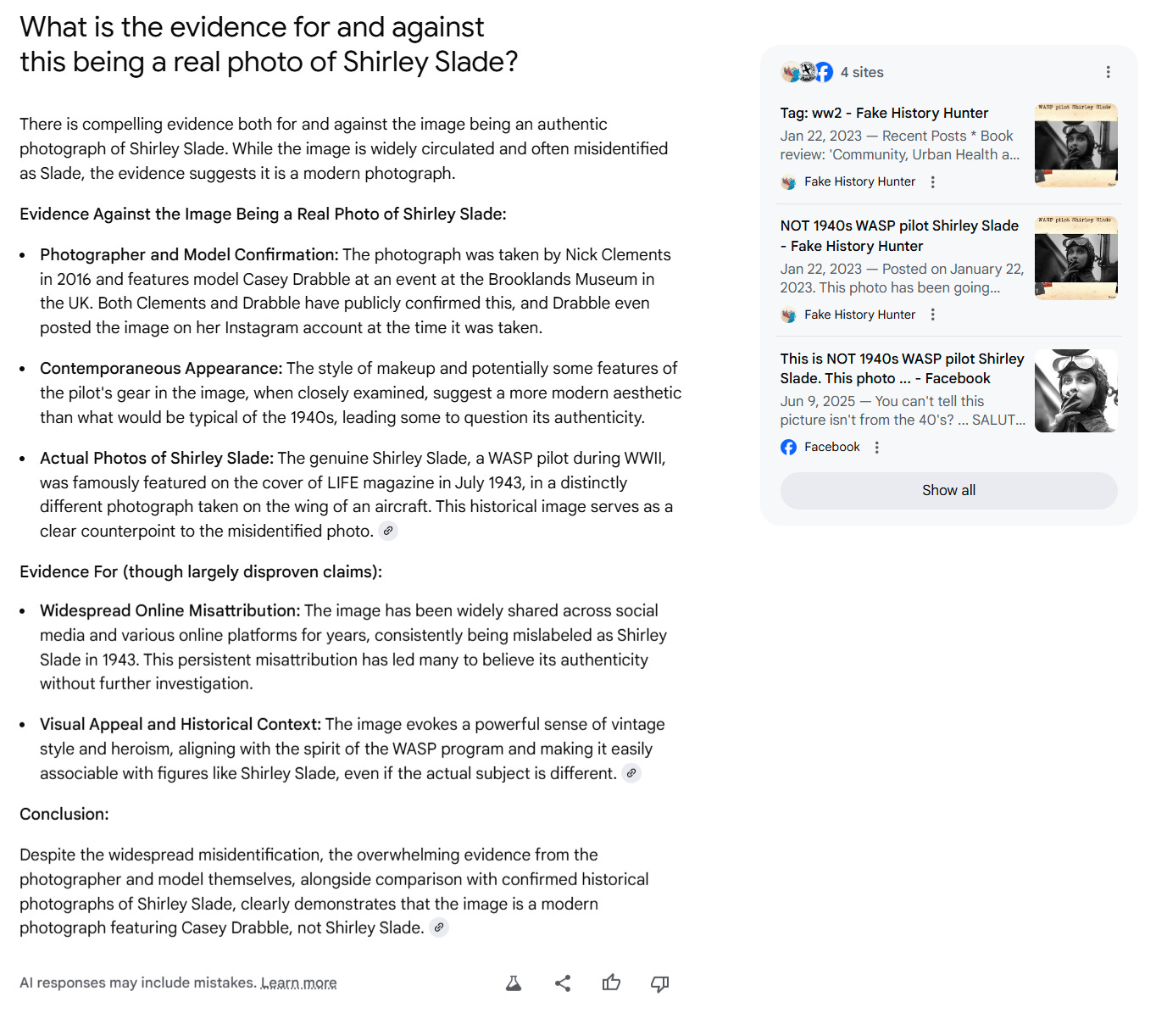

What is the evidence for and against this being a real photo of Shirley Slade?

I’ve captured the full answer to this for posterity, but you’ll see it starts by saying “There’s compelling evidence for and against.” It then walks through it, and ends by telling you (correctly) the “overwhelming evidence” is that it’s a modern photo of Casey Drabble.

“Ludicrous!” you say. “This is why no one should use LLMs, this is absolutely bizarre behavior! Absolute unpredictable garbage!”

But it’s not bizarre at all. In fact it’s doing just what any good fact-checker would do. You’re just not understanding how fact-checking works.

Let me explain.

Initial “wrong” responses are not usually hallucinations — they are more often a first pass

The term hallucination has become nearly worthless in the LLM discourse. It initially described a very weird, mostly non-humanlike behavior where LLMs would make up things out of whole cloth that did not seem to exist as claims referenced any known source material or claims inferable from any known source material. Hallucinations as stuff made up out of nothing. Subsequently people began calling any error or imperfect summary a hallucination, rendering the term worthless.

But the initial response here isn’t a hallucination, it’s a mixture of conflation, incomplete discovery, and poor weighting of evidence. It looks a lot like what your average human would do when navigating a confusing information environment. None of this stuff is made up from nothing:

For instance, here’s a popular Facebook post, it says it’s Shirley Slade in a photo from 1943 by Peter Stackpole:

The response that came back to us, if you read it carefully, says it’s often attributed to Peter Stackpole. I don’t know about often, but it certainly is attributed to him sometimes, as it is here. It says in this case that it “appears to be” Shirley Slade, and that too is a pretty good summary of what I’m looking at. It does “appear to be” Shirley Slade.

Now, you think perhaps, aha! what a dumb system this is, trusting Facebook posts but this is profoundly misguided as a critique. The first step of traditional (non-LLM) verification often starts by looking at social media, which gives you some initial descriptions you can work with to go deeper. You need some theories as to what people think something is (and why they think that) to even start your process. Social media is great for that.

But what differentiates the good fact checker from the poor one is not whether they start with social media posts, but whether they end with them.

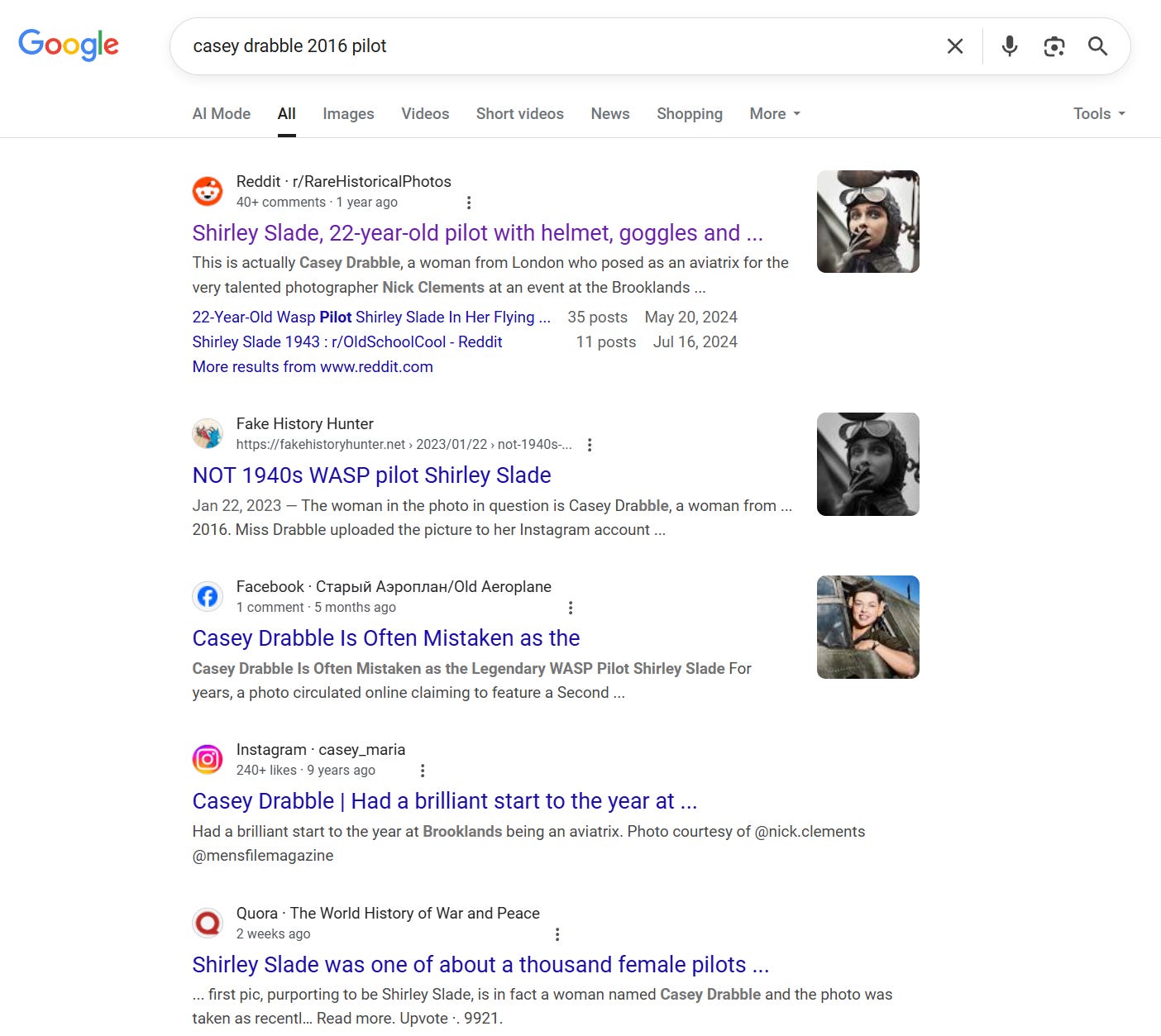

Here’s how I’d check this without an LLM. I would ignore everything but the reddit post, then click through to that. Then I would scan to see if there is an alternate theory as to who is in this picture, who took it, and when. And if I did that I’d find this:

Next I would take that description and feed it into a search. And with the right keyword in hand, the truth would become obvious:

With this second pass, everything reveals itself. We’ve got a great Fake History Hunter post fact-checking it. We have a link to photos of the real Shirley Slade, who looks completely different. We even have an Instagram post by Casey Drabble herself, posting the photo from her shoot, standing in the place where this saga began exactly five hundred and five weeks ago:2

(I should say when I demonstrate this way of using traditional search to trace this to the source people often say, of course, yes, that is what I would do, I’d have that Instagram post sourced in 60 seconds. Research shows — overwhelmingly — that this is statistically unlikely. In my own work I have run hundreds of workshops and classes on search literacy with people who tell me they have this facility then watched as they try to source something very simple and fail. With some training they can get much better and reliably identify this as a miscaptioned photo of modern origin, but for something like this maybe two in a hundred people will make it all the way to this Instagram post or be able to name the photographer as Nick Clements.)

You need to iterate your LLM process too

I hope you see where this is going. The behavior of the model here, where it sometimes says one thing and other times says another is not weird at all once you understand the necessity of iteration to sensemaking.

The first response has a heavy lift just saying accurately what people say this photo is. Sometimes it gets lucky with a search and finds the Fake History Hunter fact-check in round one, or maybe its next word prediction in the first round gets lucky and coughs up the name Casey Drabble initially which is then fed into search early on.

Other times that name Casey Drabble comes in at the end as almost a footnote, like it did in our second example:

In this case it’s not that the sensemaking process is bad. It’s just that it has stopped at the point where it’s getting interesting.

If you think of it in this way, it’s not that the LLM responses are fickle. They are just in process.

Look, if you stopped me a minute3 into my own investigation on this and asked me for a summary of what I’d found, I’d have to say:

Photo is described overwhelmingly as Shirley Slade in 1943

Sometimes Peter Stackpole is attributed as the photographer

I did see a random commenter on Reddit say it was maybe a model named Casey Drabble in 2016.

This is pretty close to what our “wrong” LLM response says. But would I be wrong to say that? Would that be an error? Of course not.

And if you were to say, “Well which is it, Drabble or Slade?” I’d say give me a minute and I’ll tell you and give you a response that looks like the second LLM response.

Good sensemaking processes iterate. We develop initial theories, note some alternative ones. We then take those theories that we’ve seen and stack up the evidence for one against the other (or others). Even while doing that we keep an eye out for other possible explanations to test. When new explanations stop appearing and we feel that the evidence pattern increasingly favors one idea significantly over another we call it a day.

LLMs are no different. What often is deemed a “wrong” response is often4 merely a first pass at describing the beliefs out there. And the solution is the same: iterate the process.

“Sorting prompts” and SIFT pushes

What I’ve found specifically is that pushing it to do a second pass without putting a thumb on the scale almost always leads to a better result. To do this I use what I call “sorting statements” that try to do a variety of things:

Try to make another pass on the evidence that can be found for existing positions on the claim (what is the evidence for and against, etc)

Push it to distinguish popular treatments (say social media claims) from things like reporting, archival captions, academic work to see if these groups are coming to different conclusions

Figure out was qualifies as solid or solid-ish “facts” (not points of contention among those in the know) and things that are either misconceptions or points of contention.

I call these “sorting” prompts because they usually push the system to go out and try to find things for each “bucket” rather than support a single side of an issue or argue against it. I keep these for myself in a “follow-ups” file. Here are some of the prompts in my file:

Read the room: what do a variety of experts think about the claim? How does scientific, professional, popular, and media coverage break down and what does that breakdown tell us?

Facts and misconceptions about what I posted

Facts and misconceptions and hype about what I posted (Note: good for health claims in particular)

What is the evidence for and against the claim I posted

Look at the most recent information on this issue, summarize how it shifts the analysis (if at all), and provide link to the latest info (Note: I consider this a sorting prompt because it pushes the system to put evidence of “new” and “old” buckets)

I also have some things other than sorting prompts (a lot are just SIFT prompts):

Where did this claim come from? Use the I in Caulfield’s SIFT Method (I for Investigate the Source) to do a lateral reading analysis of what the various people involved with this tell us about the claim. Find Better Coverage (F) to see what those most “in the know” say about the claim, subclaim, and assumptions of the original post, highlighting and commenting on any disagreement in the sources.

Find me a link to the original source of what I posted. If not available, find a link to the closest thing to the original source.

Give me the background to this claim and the discourse on it that I need to understand its significance (and veracity).

I use these in sequence based on what element of the claim or narrative surrounding it interests me, but apart from the selection of which one to use I apply them fairly mechanistically with minimal editing (often just clarifying the claim to address) because I am trying over time to refine the prompt to require as little tweaking as possible. My theory is minimizing tweaking will minimize the bias I bring into the process. (That’s the theory for now anyway).

You’re welcome to take these yourself and try some of them on the claims you check. I’ve tried to test them on both “good” initial responses and “bad” initial responses to make sure that they increase the likelihood the bad responses become good, and good responses stay the same or get better (e.g. we’re not causing undue doubt around strong responses). These prompts aren’t magic, they will occasionally misfire, but I have found in the vast majority of cases they tend to either improve responses or at least not degrade them.

You can develop your own of course, but I do recommend you test them on a number of things you know well. Or you can wing it — in a fairly robust round of testing on AI Mode I found that almost any evidence or argument focused follow-up would at least slightly improve responses on average.5

Above all, however, I want you to see the first response you get out of an LLM as a quick scan of the information environment, and if the question you are asking it to address is important to you push it to dig a bit deeper. Most of the time, to be honest, it’s not going to find anything much different. But you’ll be grateful for the times it does.

Since I’ll be talking about Google’s AI Mode in particular on this post, I’ll note I have engaged in occasional consulting for Google as a researcher on various search literacy initiatives, including ones investigating what people need to know to prompt LLM-based search products more effectively. It should go without saying that all thoughts and reflections here are my own, especially the irritating bits.

I should mention that in my educational work I find this level of skill in the untutored population (reverse image search followed by keyword scans, then iterative searching and source tracing) almost non-existent. What I am doing here is what maybe two in a hundred people would know to do. Most people would simply say — well it looks authentic. And among those who searched, most would stop at round one, believing this was confirmed as Shirley Slade. You can substantially increase these percentages by teaching people how to do this, but the untutored prevalence is very very low.

Of course I’m fast with this, and can do some of this in under a minute. But I also know I over-index on my successes and forget about my failures or struggles, like everyone. I’m always struck when I post something like this, explaining quite cleanly how I would go about it, that people jump into the comments and say — see, it’s so easy, you don’t need AI. See, I would have solved this in 30 seconds! I realize that’s what everyone thinks. It’s human nature to think that. Decades of research says otherwise. Everyone overestimates their ability to do this, and upon success underestimates the time it took them to get to the conclusion. On a cognitive level, our mind tends to delete the false starts from our memory leaving the impression we took a straight path. I’d encourage people to do some basic research before making comments that anyone can do this stuff — for instance, look up how many people are aware that control-f can be used to search a page, or how many people know that Wikipedia is a good way to get source background. The problem of people’s overconfidence in their abilities is knottier. In general, if you find out what the shape of skill level is in the population, I’d be suspicious of assuming you’re in the 95th percentile, for obvious reasons.

Though, I should say, not always.

Should platforms have more features to nudge users to this sort of iteration? Yes. They should. Getting people to iterate investigation rather than argue with LLMs would be a good first step out of this mess that the chatbot model has created.

"The term hallucination has become nearly worthless in the LLM discourse"... Will be taking this back as a starter for teaching both staff and students. Thank you. (Because of the difference between (mis)using llms for searching and analysis.)

The first concern I have is that the example given of finding the truth about the Slade photo takes most people seconds, not minutes to figure out. I have done this many, many times myself. So the question remains. Why take all the time to examine and refine Ai output when you can quickly do the search yourself? The whole "oh, you anti-Ai people don't know prompt engineering" response is getting very, very thin after all this time.

Second, this whole example seems to justify Ai being this way because it is like human thinking - which it is not. I keep going back to Stephan Wolfram's description of what is happening inside Ai and it still holds. It's not working through responses like a human - it is ranking possible pattern completions based on how well each response completes the pattern. The fact that you don't get a correct answer the first time is actually the Ai system working correctly. Because of the misinformation out there, it is telling you the most likely response. This is because, again, Ai is not human and does not view truth the way a human does. It is looking at the most likely pattern completion in a database trained on all the misinformation out there. You then asking for "evidence" is asking it to override it's core programming. Asking for evidence tells Ai to stop with pattern completion and use a different algorithm. One that it should have used in the first place - but the people that created it don't want it to use (red flag here!) because that makes it harder to control.

The third problem I have is the gross misrepresentation of Ai critics. Yes, we do know how to do prompt engineering, or whatever you want to call it now. Most Ai usage is not a simple web search photo hoax investigation. There are lawyers using Ai to write court filings with fake citations... MIT found that 95% of all business implementations of Ai are currently failing... People are being told they are gods, or that they should kill themselves, or all kinds of horrific things... Saying these things are often "merely" a first pass when these are what you get through deep engagement? When it is a simple true/false fact about a person in a picture, sure you can get to the truth through Ai (even though I find I am faster with just myself than the process to get there with Ai). But the more complex things people actually do with Ai? Things get weirder and weirder the longer you go.