Reasonableness #2: What are we defending, exactly?

We often shorthand what we are defending as the "claim", but we are defending a position relative to a claim, and that has ramifications

Part of a series, see the first post here and second here.

In the last post I talked about argument as an attempt to enhance the reasonableness of a position towards a claim. That’s a lot of words, and I don’t blame you for thinking its a rather verbose phrase. In particular, why not just say “enhance the reasonableness of a claim?”

The truth is I do say that sometimes, as a bit of shorthand. But the lengthy version here has a precision that has important ramifications. This post attempts to detail what a position towards a claim is, and why the idea of defending a position is so crucial to productive thing about argument.

Propositions, assertions, claims

Let’s start with some terminology.

Propositions are neutral statements, with no position attached to them. “There are 382 licks to the center of a Tootsie Pop,” or, conversely, “The number of licks to the center of a Tootsie Pop is fundamentally unknowable.” In proposition form, we treat this not as a statement of fact but rather a statement up for debate. (If it helps, imagine it as “For discussion: There are 382 licks to the center of a Tootsie Pop.”)

When we state one of these is true, it is an assertion. It’s a proposition, but it now is attached to a position. “It’s true that there are 382 licks to the center of a Tootsie Pop.” We can assert the inverse as well “It’s false that there are 382 licks…” etc.

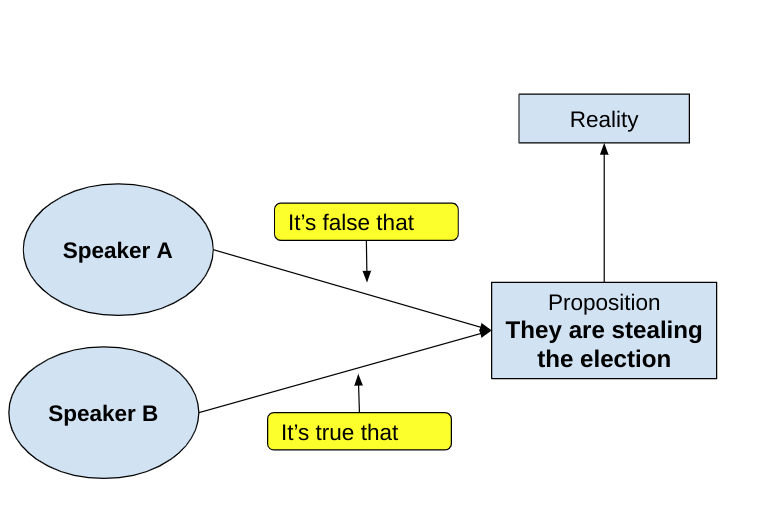

Following so far? Hopefully this all sounds simple, but we’re actually speed-running some philosophical concepts here. Let’s ditch our Tootsie Pop example, and talk about elections to review. First there is a proposition, which has a relationship to reality (see notes for more nuance here):

However, then there is our position on the proposition. This initially will seem like it’s unnecessarily complex, but all will be revealed in time.

Or,

There’s a host of reasons why we separate out the position from the proposition. A simple one is so we can see that both the people above are discussing the same proposition. That is, when you say they are stealing the election and I say they aren’t we are not discussing two different propositions, but rather two different positions on the same proposition.

However, another reason to separate these out is that there are positions that are broader than true/false judgments. We can think of assertion as one type of propositional attitude (as I believe Bertrand Russell was the first to show). But following more recent work in argumentation theory it is possible to see a wider array of attitudes. How much wider an array is some matter of debate. At the very least, we could see various attitudes of doubt or conditional belief in the mix. “I doubt they are stealing the election” or “Presumably they are stealing the election.” Some theorists want to go further — “I fear they are stealing the election” etc. For the sake of simplifying vocabulary I use the terms position and propositional attitude interchangeably.

So what’s a claim? I go back and forth on this usage, but for the most part I follow Toulmin, who sees a claim as a proposition on which someone has adopted a position requiring defense. That is a “proposition” is a philosophical object, a “claim” is a discourse object.

OK, great, so what does all this mean in real terms?

#1: Doubt is just another position

Let’s start with this. In a world without propositional attitudes doubt is often accorded a special place. E.g. you can assert something is true or that something is false, or you could “choose to assert nothing”, e.g. “doubt” that something is true.

Once we see that asserted belief and non-belief are propositional attitudes just like doubt, it becomes clear that doubt is just another position, one requiring its own defense. When we say we doubt something, what we are saying is that given Proposition X and our existing knowledge of the world that a reasonable position towards X is doubt, just like when we say that X is true we are are saying an reasonable position towards X is belief.

Again, the question under debate is not whether Proposition X is true. The question is what the reasonable position on Proposition X is. Given three options — “it’s possible that”, “it’s true that”, and “it’s unlikely that” — it’s probable that one position is more reasonable than the others, and it’s the position we are debating.

Doubt is fundamentally different from saying that one has no position. To have no position is to express that you do not have enough information to determine what would constitute a reasonable position (something people do far too infrequently). There are times when doubt is the most reasonable position, times where neither belief or disbelief are defensible. And there are times where doubt is not a reasonable position.

#2: Argument (often) pulls one towards a favored position, not into it

Putting aside propositional attitudes like “fear” or “hope” for the moment — for a set of attitudes that express various levels of commitment to a proposition (false, presumably not, unlikely, possibly, probably, presumably, true) persuasive argument is often about motion along a gradient. For instance, if I take the position something is likely and you are of the position that that it is unlikely I may be happier if you come to believe it is possible, even if you do not reach my preferred position. My perception may be that the shorter distance on the gradient makes my position more comprehensible, or that I believe that an imperfectly reasonable position is at least less dangerous to yourself or others.

As such, I’m not always arguing for the position I inhabit. If a person believes firmly that vaccines cause autism, my argument may be designed to enhance the reasonableness of a position of doubt regarding that proposition. That may be because I think that doubt is both more reasonable and less dangerous than the belief the other person holds.

One important aspect of this is that it is important to separate the position argued for and the belief of the arguer. Even where a speaker is being genuine and transparent — i.e. not using deceit — there is often a gap between what the speaker believes and what is argued. For example, a person who believes the election is stolen may spend their time arguing that believing that it is possible the election was stolen is reasonable. This does not mean this is their position.

Take the case of the family member I mentioned last post — they likely believed the vaccine was on net harmful, but argued to me that it was unclear whether it was helpful or safe. Likewise, I was very sure of its benefits, but if I was to describe what I was doing in those conversations it was geared to make the position that it was likely a good idea to get it appear reasonable. Far from expressing our beliefs, we were both actively minimizing them in an effort to focus on what we each believed was an achievable goal — to demonstrate that some intermediate position was more reasonable than the position the other person currently inhabited.

#3: Positions are often about discourse status of claims, not facts

This part blew my mind when I first encountered it in Toulmin’s Uses of Argument.

Let’s say my bike disappears. You say maybe someone borrowed it, and will bring it back. I say, yeah, I don’t think that’s likely, I’m sure it was stolen. You say, no I really think it’s possible — your neighbor Jane borrowed my bike without asking once, maybe it’s her.

What’s going on here?

Toulmin talks about this in a long chapter in Uses. The prevailing fashion of the time was to see this sort of conversation as expressing probabilities. Sometimes we do do that of course. If I say “It’s likely to rain” and you say “It’s unlikely to rain” I may be saying something like “There is a 75% chance it will rain” and you might be saying something like “There is a 25% chance of rain.”

But that’s not what’s going on in the bike scenario. Instead the language of probability is being used to circumscribe the reasonable positions relative to a claim.

When I say I am sure it was stolen, what I am saying is there is only one reasonable position on the claim “The bike was stolen.” When you say it’s possible someone borrowed it, you are saying that while the most reasonable belief is maybe that it was stolen, the belief that it was borrowed deserves continued consideration.

When I say something is unlikely, I mean, more or less, that an assertion that it is true isn’t worth much consideration. When I say it is probable, I mean to say an assertion of truth is the best position, but evidence may exist that could call that position into doubt. When I say “presumably” something is true, I’m expressing that to unseat that position you’d have to bring some unexpected evidence I am currently unaware.

This gets a bit muddled, as Toulmin’s “qualifiers” and “propositional attitudes” aren’t exactly the same. But once you see that the terms often express the relative reasonableness of opposing positions you can’t unsee it. Take the lab-leak theory of Covid. If someone says that’s possible, immediately we jump to odds. How possible? 10%? 50%? But the odds are a retcon, aren’t they? Very few people are really sitting around thinking “What’s the best term to express my belief that there is a one in five chance that Covid escaped from a lab?” Something that is “unlikely” is an unreasonable position that deserves little attention or exploration, failing dramatic new evidence. Something that is possible is not necessarily the most reasonable position, but is reasonable enough to argue.

Again, I am crossing Toulmin’s qualifiers and propositional attitudes here in ways that probably make philosophers wince, and what’s more I’m taking the concept of reasonableness and retroactively applying it to work from the 1950’s.

But it’s a blog post, not a paper, and what I want to explore here is this idea that argumentation is not about “proving” a point, but rather about “enhancing the reasonableness of a position”.

#4: Enhancing a position means enhancing it, not proving it

This brings me to my last point, and one that relates to the first post of this series on endless argument. If you read that, you’ll recall that one of the main points of it was that both online and in offline life we engage in extended arguments, proposing evidence to support our position on various claims. When a person mentions that the new car — a subject of some dissent — is getting an unexpectedly good gas mileage that is not to say that that fact alone proves the car was a good buy. Rather, it is an attempt to make the position that the car was a good buy moderately more reasonable. What’s at issue when the new evidence is introduced is something that looks a bit more like “Should these bits of evidence being introduced over time substantially shift the reasonableness of the position argued for?” And a lot of our disagreement is over that “substantial” bit.

I hope to deal more explicitly with the concept of evidence in the next post, and talk a bit about how we evaluate the meaning and importance of evidence.

See the other posts in this series here and here.

Notes

There’s a bunch in this post that is a bit of a mess — I’m taking this idea of reasonableness and applying it to a bunch of stuff over a century or so of thought. And there’s a particular mess in this post around position, which I am simultaneously using as a first order thing (an orientation towards claims) and a second order thing (an assessment of the appropriate ranking of orientations towards claims). It’s something I’ll have to think about how to clean that up, because it involves two separate sets of insights I would like to keep.

As before, I pull a lot of ideas here from argumentation theory, and attempt to synthesize them in light of challenges I’ve seen in misinformation studies. I don’t claim any of this stuff to be new, though when I look at conversations around rumor, misinformation, and the like, I see some relatively established insights at the intersection of philosophy and rhetoric are not being utilized, and in many cases a lack of attention to these elements of what argument actually is have been skipped, to the detriment of the field. So hopefully this opens a conversation.