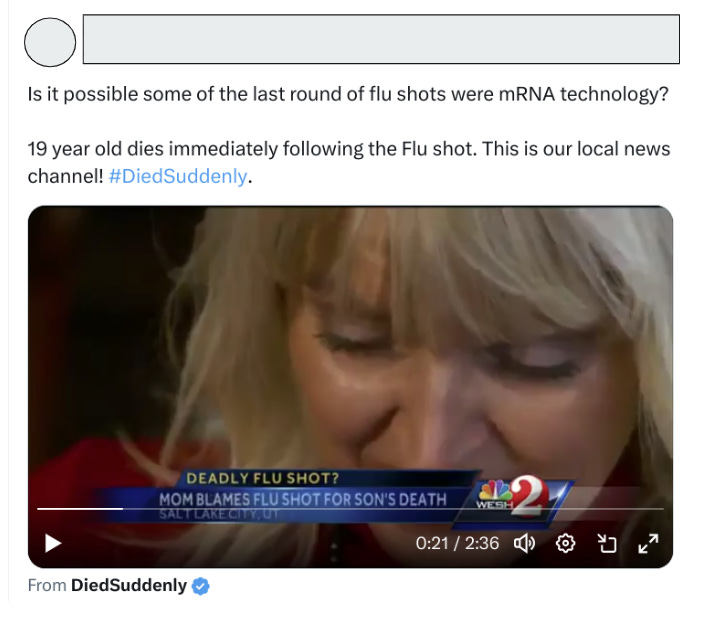

So this came across my feed yesterday:

There's a lot going on here. We're going to diagram it in a minute. But let's start with the basics.

How open arguments work

In order to analyze this, you first have to realize it does not stand alone. It is part of an ongoing argument that is being constructed. The way that such arguments work is pretty simple.

Say I want to convince you that Sally is not a good realtor. We chose her as our realtor, but I think she’s not on top of things. You think she’s more or less OK. Still… she sent us the wrong form yesterday. She returned one of our calls late, possibly ruining our chance to see a house in time to make an offer. When a house we had been interested in had it's price drop, she didn't think to notify us.

I make an argument to you that sounds more or less like this.

The structure is simple. My grounds is "Sally messes up a lot." To support that I have many examples, here labeled "E" (for, you guessed it, examples). At some number and quality of examples, the argument would be well-grounded, provided that the examples match the warrant here, and aren't a) just the usual errors, or b) errors with little impact.

Here, for "backing", I map out the stuff I mention above: she sent us the wrong form, she didn’t return a call of ours, making us late on getting an offer in. She didn’t seem to know about a house she should have known about.

Central to this argument is the "warrant" that Sally is not just having the normal, expected level of error. That means the more examples I can come up with (and the more consequential the examples) the stronger the argument.

So what about the “ongoing” bit? Well, maybe I make this argument and you’re unimpressed. That’s a few things Sally got wrong, but so what?

As long as we still have Sally a a realtor, this argument is likely to stay “open”. If we show up for a viewing, and Sally is 20 minutes late, I’m adding that to my list. If she shows up without the correct sell sheet, I’m trying to catch your eye, and say “see what I’m saying?”

I’m engaging in “evidence foraging” over time, trying to bolster my argument through the collection of additional examples. For someone that believes that Sally is incompetent, each example further solidifies or maintains that belief. For someone who thinks Sally is OK, each piece of evidence makes them a bit less sure of that.

The structure of the #DiedSuddenly argument

Hashtags on Twitter are often used in a similar way. In the case of #DiedSuddenly, the hashtag often identifies a submission into evidence. So the overall argument looks like this:

Like the Sally the Bad Realtor argument, the person that advances an argument like this is not saying any single given piece of evidence proves the shot is deadly, any more than Sally being late once makes her a bad realtor. Each time a new piece of evidence is introduced the assertion is something more like "This new piece of evidence makes what I am arguing significantly more reasonable."

Hence, the question isn't whether the death of Marvin Hagler after a vaccination or the heart attack of a pilot proves the vaccine is deadly, but rather, do each of these events mentioned significantly increase the strength of the case that the vaccine is deadly. As we'll see in a moment, the answer for the ones we've poked at is nope. But it's important to fairly characterize the argument all the same.

The specific example

OK, lets get to our specific example. As you'll remember it was this:

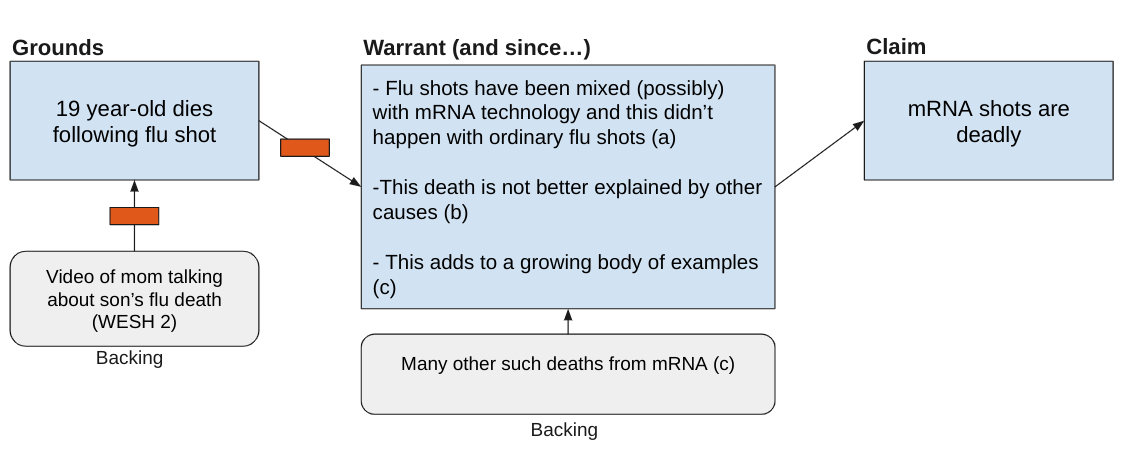

And we can map this out like so:

In this case, the video is reporting that acts as backing for the larger subclaim that a 19 year old died of a flu shot. That event supposedly adds to the "mounting evidence" that the mRNA shots are unsafe.

How does this argument fail? In a number of ways. But the most obvious is this: the story about the flu death is not recent – it is from 2013, almost a decade before mRNA shots were rolled out.

That's probably all you need to know here -- for the person using this of evidence of mRNA danger that’s game, set, match. A total loss. But for those interested, the argument is wrong in yet another way. The news coverage of this event in 2011 highlights that the “death by flu shot” is a hypothesis of the mother of the person who died, one that is disputed by the experts quoted in pieces we read on this. The news story doesn’t really support the idea that this is a death from a flu shot, never mind the the result of an mRNA shots that wouldn't be available for another ten years.

We can note both these problems like so:

Finally, we come back to the fact that this argument is an incremental argument – that is, the person making this argument is not claiming that this death alone proves that the mRNA is a deadly vaccine. A with the realtor example, they are claiming that it adds to a growing body of evidence that this is a deadly vaccine.

And this is where it gets interesting. Because that “growing body of evidence”? It mostly looks like this example – events that are put forth as evidence of mRNA vaccine death, but when looked at even a bit more closely turn out to be misrepresented. What happens is each new one of these “#DiedSuddenly” incidents get uncritically accepted, and becomes backing for the argument that makes the next piece of weak or misrepresented evidence seem more meaningful or plausible. But nonsense built brick by brick is still nonsense.

This is perhaps the one area that is at least a bit harder of a call. It’s possible, of course, that someone could come up with some better backing for the idea that the sort of death proposed here is common, but from the perspective of the hashtag, I don’t see it.

In any case, we can note the following failures of the argument like so:

Key:

I: Video and associated news coverage does not support claim of vaccine death

II: Vaccine in example unrelated to mRNA technology, does not connect to warrant

III: No real evidence that this is part of a larger trend, at least as expressed here. There might, of course, be alternative backing not brought to bear here, but we’re unaware of it.

Note there’s more here we could do — there is no backing for the idea that flu shots are now based on mRNA technology (another failure of the warrant). Likewise, the argument struggles with the level of counter-evidence to its claim. In the U.S., 80% of the population has at least one dose of the COVID vaccine, the vast majority of that was mRNA. If deaths resulted even one hundreth of one percent of the time (0.0001) that would be tens of thousands of deaths. Early in the pandemic, before the vaccine was widely used, it might have been possible to make this case; it seems very difficult to make it now.

More to Come

If you want to make God laugh, tell her your proposed posting schedule. But here’s the plan at the moment. Over the next months I want to take arguments I find online and show how modeling them and talking about their structure can help identify their weaknesses and strengths, and get us beyond simplistic misinformation frames to more substantial analysis. Along the way I’ll share what I’ve learned from over a decade of analyzing online argument. That’s the plan at least.