How foreground-swapping can improve LLM response usability

Using the dynamics of foreground and background content to create a "web of correction"

One of the more frustrating elements of LLM responses is how they will tell you one thing, and then when pressed on whether it is true say “Oh, no, that’s ridiculous! Who ever told you that nonsense?”

A favorite example of mine no longer occurs, but it used to be if you asked Google if Emma Thompson played the mom in The Parent Trap that AI Overview would sometimes tell you “No, the mom was played by Natasha Richardson. Emma Thompson is often thought to be the mom, but she was only a writer and producer on the film.” Then if you asked “Was Emma Thompson a writer and producer on The Parent Trap?” It would tell you “No, of course not, The Parent Trap was written by David Swift, Nancy Meyers, and Charles Shyer. How are you so misinformed?”

This seems maddening and arbitrary if you think of the LLM speaking from a place of knowledge, and has produced a bit of ridicule. But like so much of our dumb conversation around this technology, the talk around these errors tends not to have a lot of curiosity to it. The LLM isn’t an intelligence, after all, so an obvious question is why does the system appear to “know” contradictory things here? What can we learn if instead of immediately dunking on this we ask why do we get one answer in one case and another answer in another?

The Foreground/Background Two-Step

To conceptualize an answer to this, in previous posts I introduced the idea of foreground and background content, where foreground content is the material directly addressing the query and the background content is the supporting detail.

How does this help explain things? We are going to anthropomorphize a bit here, but I think helpfully.

Say you are a person who has a lot of very fuzzy knowledge about nearly every film ever made. It’s extremely broad knowledge, but everything that you know just kind of comes to you without any sense of source or certainty and you’re often wrong.

I put you in a room with a search engine and a phone and tell you that you have to answer questions about films with a search engine and whatever you know. You are required to produce not only a simple answer to the question but a detailed answer to the question. Let’s say five paragraphs supporting your answer.

Here’s the catch though: you only get three searches to do this, and you only get to click on and read in full two pages. The rest of your knowledge will come from scanning the little snippets that come back in search. And the way you get judged on the answer that 80% of your grade is going to be whether you got the main question right and 20% of your grade is going to be whether you get the supporting details right.

What’s going to be your strategy?

I’m not saying this is exactly how LLMs go about it, but I want to show the tradeoffs here. Your best strategy is going to be to

Think about what you might say without a search engine.

Use a search engine to investigate those ideas and look for others.

For supporting detail, use what you found doing the main searches, making a lot of justified guesses based on what you kind-of-sort-of remember

What’s going to happen next is predictable. You’ll be pretty good at getting the information that is central to the question right. Asked “What lines in The Empire Strikes Back are improvised, if any?” you’re going to search and see that the most famous line described as improvised is (by far) Harrison Ford’s “I know.” line. In the process of verifying that with your allotted searches and page reads you’ll see that Lucas initially hated the switch, and that Carrie Fisher was unaware that was going to be the line and was a bit peeved about that. You’ll have seen in some of the search snippets that the initial line was “I love you too.” In describing it based on skimming your three allowed search results and your two allowed full page reads you might say:

The best example is the iconic “I know” line voiced by Han Solo, in response to Leia’s “I love you.” The line was initially “I love you too” and a later idea for the line was “I’ll be back for you”. Hating both lines and feeling they were wrong for the character, when it came time to say it Ford improvised “I know” on the spot, shocking Carrie Fisher whose reaction is captured in the scene.

If you are just looking through the search results, that’s going to seem a pretty good summary, at least at a skim. Much of that comes from solid sources, but to produce a coherent paragraph you have to create some connective tissue and background that is at best coming from 20 words you saw in a search snippet and at worst coming from that kind-of-sort-of memory you have of the thing.

Still, it’s pretty good, right?

So you provide that answer to the person on the phone.

The person then asks you: “Is it really true that when it came time to say it Ford improvised “I know” on the spot?”

Well, I did just say that, right?

But now I have three new searches at my disposal and two more full page reads, and a new foreground focus for accuracy. The question is no longer “Which line in the film?” but rather “Can this particular line be accurately described as ‘on the spot’?”

You do your searches and your additional reads and reply:

“On the spot” is not a correct description. Harrison Ford did come up the iconic “I know” line in The Empire Strikes Back, but it wasn’t an ad-lib; it was a collaborative suggestion with director Irvin Kershner, replacing the planned. Ford suggested it immediately before filming a set of alternate line takes for the scene, the director agreed and they filmed it.

From the perspective of the person on the phone, maybe this seems to speak to your reliability. But when you step back it’s honestly weird we think this is weird, because as any writer can tell you, this is very similar to how we write.

We answer one question, we step and look at the lines and ask ourselves “Is it really correct to say that subclaim?” and then we look at that and just as often as not the answer is “not quite”. And we keep doing that until the lines left to poke at stop bubbling up revisions. At least that’s how I write. It’s a constant process of getting what I think I know out on the page, in a way that often feels like I am an LLM with one word flowing to the next. While I am typing supporting detail I’m looking at what is appearing on the page and asking “can I say that for sure?” and now that is my foreground task as I go out and search, verify, and revise.

The difference is, of course, that many people still see LLM responses as a publication, the end result after all that stuff has been done. And if you use intensive reasoning models you can, at somewhat substantial expense, get most of that stuff done before the user looks at any of it.

I’m not sure that most people who haven’t paid for models realize this. If you are curious about the future of this technology and you’ve never used something like Claude’s Opus 4.5 or GPT 5 Pro, you really should. These systems do a lot of complex reasoning but the biggest thing they do is produce output, then take the subclaims of that output and feed them back in repeatedly asking “is what I just said quite right?” And if you let them do enough cycles of that you’ll run up a big API bill but you’ll also get output that is a bit more publication quality and less middle-of-the-process quality.

This is also the core engine underlying my automated fact-checkers. We take some output and find the associated claims in it and then push on each one individually while giving some guidance to the LLM on what constitutes supporting evidence. There are variations on this. Deep Background leans more into unstated claims, assumptions, and presuppositions. The recent line by line fact-checkers I’ve been building lean into subclaims of larger blocks of text. And again, there’s lots of little things in all of these to make that cycling through as accurate and efficient as possible, but this background to foreground recursion is the basic engine.

So one way to see these LLM assertions followed by negation of those assertions when asked specifically about them is believe that is shows how bad LLMs are. Another way to see it as a pattern of error and accuracy that you can use to your benefit.

Getting around hallucinated sources with foreground-swapping

Which brings me to my latest realization. Lately I’ve been using Claude Opus 4.5 to do markups of LLM responses from Gemini, Claude, and ChatGPT on film questions.

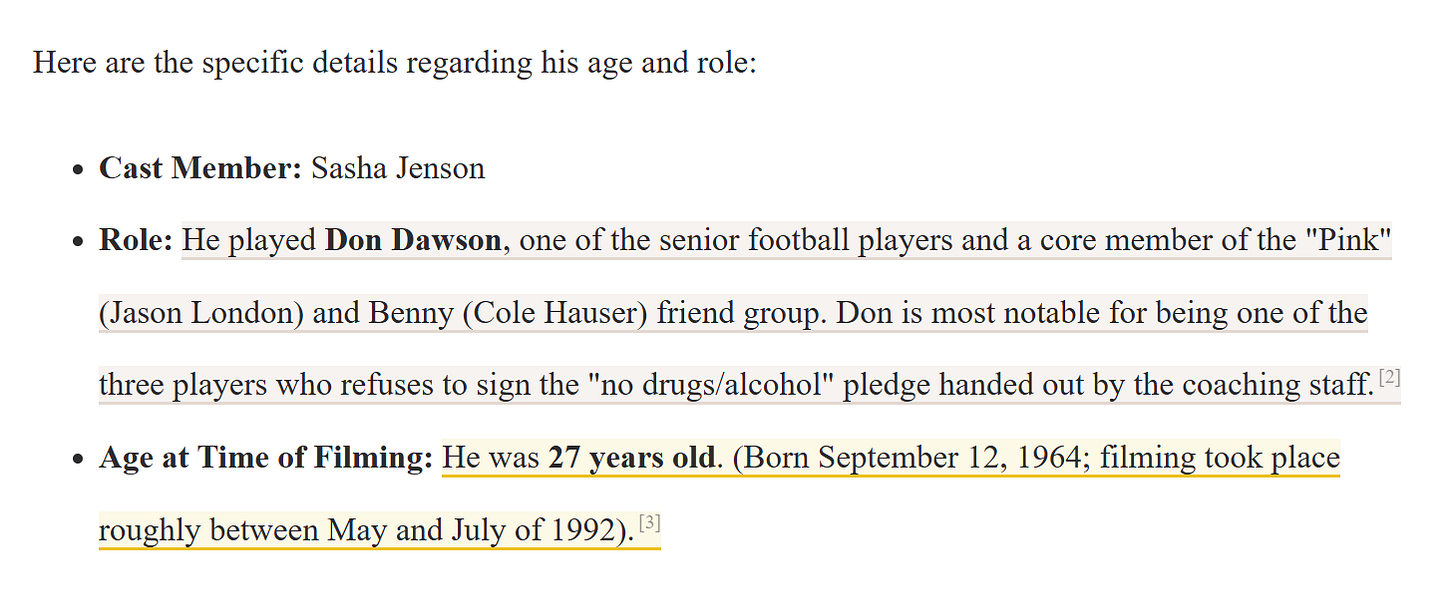

I ask a question of an LLM like “who was the oldest member of the Dazed and Confused cast”, and get a response. I then have Claude Sonnet or Opus 4.5 go through each sentence and check it. It’s pretty cool. Here, for example, it notes a problem with the yellow-highlighted line:

We hover and see the issue: the birth data is wrong.

My initial design was to have each of these items linked to a footnote with a source that supported the annotation. With Claude’s Sonnet 4.5, I was able to do that, mostly. Claude, if you don’t know, doesn’t skimp on searching or reading pages, and when asked for sources doesn’t simply provide URLs that it guesses might address the issue, it provides the real URLs to pages it has read during its search session, and it searches a lot. If you think about our analogy above with the questions and the phone line, Claude is allowed to go hogwild on the searching and the retrieval.

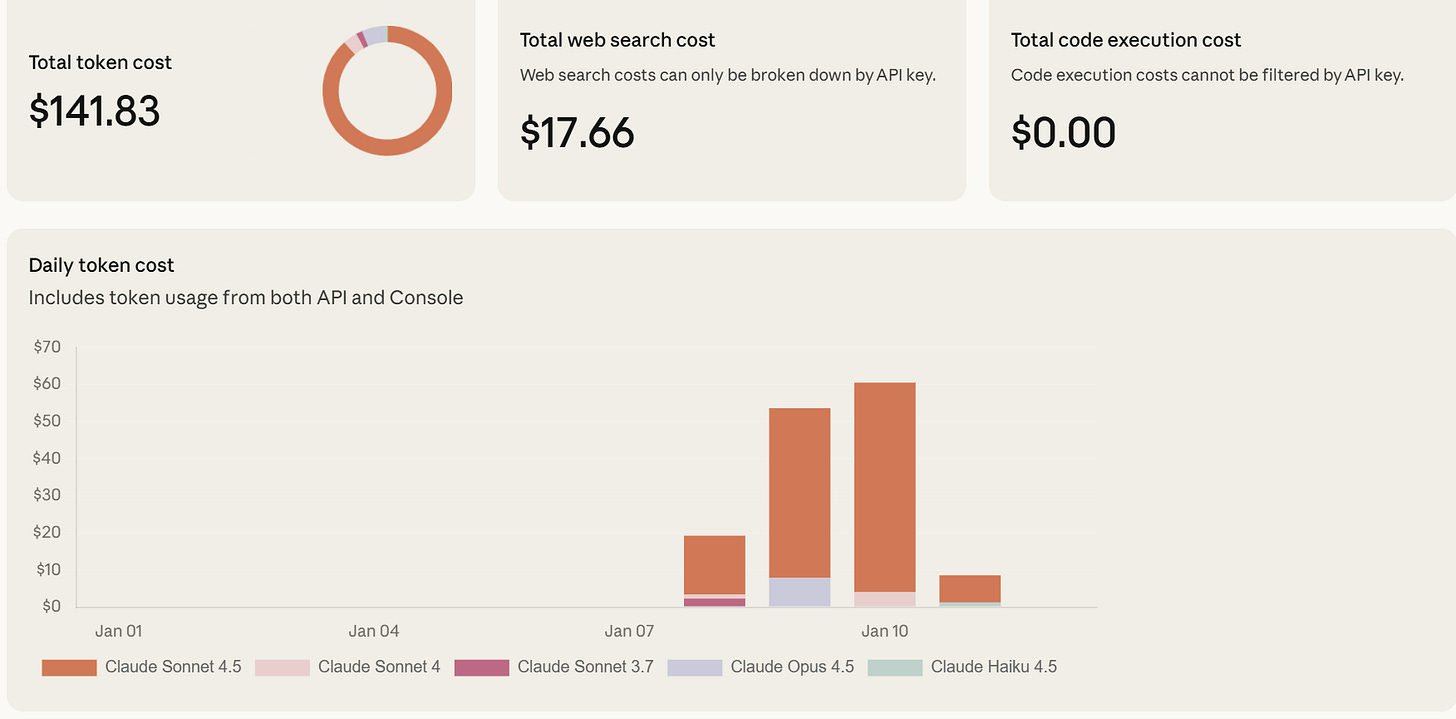

The flip side is because Claude is processing hundreds of search results and dozens of full pages it uses a ton of tokens. There’s a web search cost, but the bigger cost is when your model is really fully reading and processing these search results you’re paying for every word of every page it “reads” and you get to a million tokens really fast. So over a couple of evenings I ran 167 reports on LLM output using Claude Sonnet 4.5 and they were absolutely gorgeous, and in most cases, I could have pulled perfect supporting links for my footnotes. But here’s what that weekend experiment cost me: about a dollar a fact-check.

I think if I was trying to fact-check something for personal publication this would be a heck of a deal. One dollar a page and it provides a link for every claim and flags ones that aren’t quite right? Are you kidding?1

But for something on this scale, where I’m experimenting, it’s going to bankrupt me.

Meanwhile, using Gemini Pro 3 Preview gave strong results with a couple caveats. I couldn’t get it to go line-by-line (but it usually picked the right claims to check). The biggest problem? When asked for supporting links about 10% of the time (very rough estimate) it hallucinated them.

On the other hand, the Gemini responses are cheap. The billing API isn’t as real-time as Claude, so it will take a while to sort out costs, but I think this represents about 600 reports run, so close to a dime a page:

That still was an expensive week (and a bit frustrating, because I can’t get past Tier 1 status, which mean my batch processes top out at 200 requests a day). But a dime an analysis puts us in a whole different territory.

One of the things I realized through poking at the analyses was that for all its hallucinated links, Gemini wasn’t actually wasn’t that much less accurate than the more intensive Claude process. It just couldn’t source its decisions.

That’s when I realized that I could use background/foreground swapping another way. Even though AI Mode (and especially AI Overview) were not more rigorous or accurate than the Gemini 3 Flash Preview responses I was testing, they didn’t have to be. Gemini 3 Pro Preview could identify errors and missing context in the LLM responses, then construct a search query that foregrounded the disputed fact. And when the at-issue fact was foregrounded, then AI Mode and AI Summary could provide a strong response and great links.2

I actually didn’t need footnotes, because once the issue was properly foregrounded a query could take care of the rest.

I’m sorry but you have to watch the video

I’ve noticed something with my posts, and that’s that you are all readers. I will get 5,000 visitors to a page, but if I put a video in that page I’ll get 100 views on it.

I know. I feel the same way. I do the same thing. I will read a 10,000 word essay before I will watch a two minute video. But the point I want to make here is about a way to design information systems that answers the question “What good is an LLM if I need to verify everything in a response?” and the answer is that you can stack an LLM on top of an LLM and rather than compounding error it substantially mitigates error, especially if we keep the human in the loop. This is just one more way that it true. But in order to understand that you are going to have to click play below.

Try it out yourself

I’ll probably be using this site I built to explore both the nature of LLM error and strategies to deal with it over the coming weeks. But you’re also welcome to poke around in it yourself, provided you read the caveats. The site is not an evaluation of “how accurate LLMs are” and really can’t be. It’s a site I am going to use for two things: to better understand the failure modes of different types of LLMs and to better understand how automated LLM response checking might surface and address those errors.

If you understand that, and are the sort of person who is interested in error, rather than a person who uses error as a way to dismiss things from their mind entirely, then I encourage you to click the link. If you watch the video you’ll see how I browse it, and what I find interesting about it. If you want to just wait for whatever posts I write in the future on it, that’s fine too. But I think what you’ll find is most places that an error is identified:

that pushing that foreground description to AIO or AIM results in a good response and good sources:

One problem I am still having is that Gemini Pro is going a little light on the errors. For example, other aspects of that “summary” of Variety are also made up, including the “electric chemistry” bit (which might just have been pulled as a general descriptor or might be from a Screen Rant review in 2022) and “the appeal of the soundtrack.” The Variety review is in fact just a three-paragraph note, which is indeed “mixed-to-positive” but says none of these things. It would be nice if the check could catch all of these.

The other problem I’m having is that Gemini is seemingly refusing to upgrade me to tier two which means I am severely limited on the number of Gemini Pro runs I can do. If someone knows how I can get the system to realize I’m hitting limits and invite me to tier two status, let me know how in the comments. I’d love to have enough headroom that I could regenerate a lot of the site.

If you think that is expensive I am guessing you have never worked with professional fact-checkers. Their hourly rate (about $50 an hour) is high enough that before they start checking your work you provide a link for every potentially disputed claim in your work, because you do not want to be paying them by the hour to track down sources if you can avoid it, only to verify the ones you have. And yet Claude will take a page with no sources at all, fact-check it and link it up for a dollar. If you’re not using these tools to fact-check — or perhaps pre-fact-check your own work, I think at this point it’s verging on negligence.

Not to go all Inception here, but to be more precise, AI Overview provides a good response to the foregrounded question and good links to the foregrounded question but is obviously much less trustworthy on the backgrounded question.

Trying to understand this. You use Gemini 3 Pro Preview to identify errors and "fact check" but you don't trust it to generate URLs to the source. So instead you make it "foreground the query" and when user clicks it runs AI overview?

Your foreground, and background theory is interesting. So the theory is if you ask the LLM directly something, it usually wont hallucinate, but it might do so for something "background"/auxiliary detail that your question didn't ask directly. That feels very human, the parts I search and see I get right, but the rest of my answer where I "fill in the blanks" with my memory (pretraining knowledge) and it might be wrong?

On Dazed and Confused, did you supply a definition of "cast" as the top x named characters? A birthdate in the 1960s didn't sound right to me, as I vaguely remembered some scenes with teachers in them. Wouldn't there have been some teachers who were older?

IMDB + Wikipedia didn't give me the right answer quickly, but it at least established that Terry Mross (Coach Conrad) was born in 1951.