SIFT for AI: Introduction and Pedagogy

Once I thought more deeply about what people had been asking for it made a lot of sense

One of what I think will be two posts on the idea of “SIFT for AI” and what that means to me.

I think the lowest point in my recent information literacy career arc was probably the presentation I did for Plymouth State’s statewide information literacy conference in October 2024.

They were lovely people there. The conference was great. But my keynote presentation wasn’t any good.

I could make excuses, of course. The microphone kept cutting out and it threw me off my pace. I was jet-lagged. I stayed the night before in a bed and breakfast that was adorably 1800s (good) and also had a bed from the 1800s (bad).

But the biggest problem was I had lost my zip.

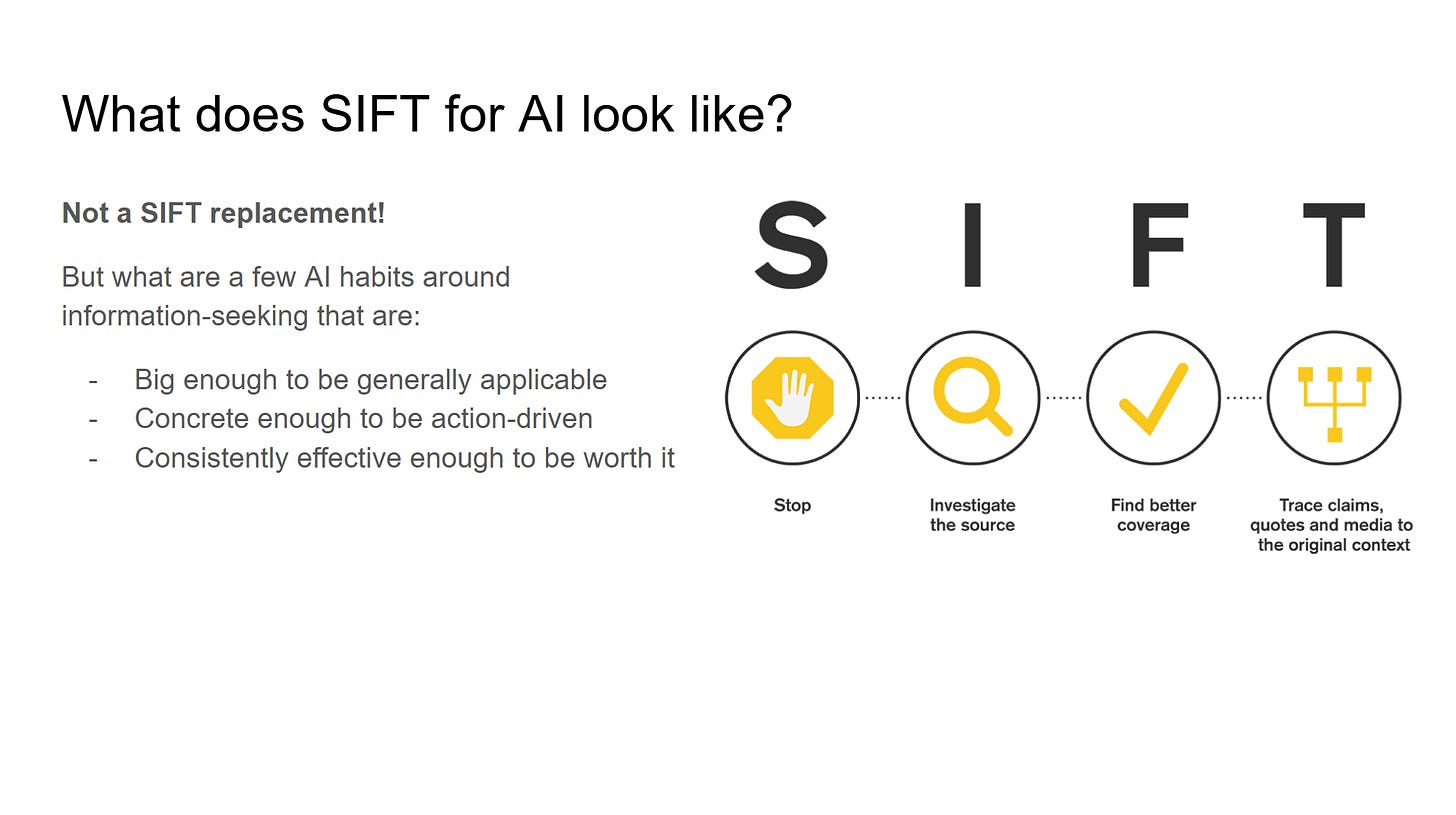

I came there wanting to talk about SIFT, search, and the like. Everyone else wanted to know “What does SIFT for AI look like?” I was grumpy about it and peeved. It wasn’t a new problem. People had been asking me that question since 2022. In an ironic twist of fate, Sam Wineburg and I had sent our final pages of our book Verified into the publisher a week before ChatGPT was released. After seeing the ChatGPT launch we begged the publisher to let us insert six pages of postscript. They agreed.

I still think those pages written three years ago are some of the most spot on prediction of where the world ended up in 2025 and what skills it would require (if you have a copy, pull it out and read it — it’s surprisingly good!). From 2022 on I stayed engaged with AI, and watched it develop. Wrote think-pieces about how it should interact with search. But everywhere I went, there was this question — “What is SIFT for AI?”, which seemed such a meaningless question. And I would hold the line — look, the SIFT of AI is SIFT! You don’t have to change!

For some reason at Plymouth State, I suddenly saw it differently. Was I going to become the Fat Elvis of SIFT, rehashing out the hits? Be Mick Jagger, chicken-strutting to “Start Me Up” for the next few decades? Or was I going to finally seriously engage with this question people kept asking — for which they really wanted and valued my opinion?

SIFT is amazing. The success of it and the broad adoption of it changed my life. I still love it. But it has become so ubiquitous in the world of information literacy that half the time it is mentioned I’m not even referenced anymore. People use it, but they don’t need me to teach it. If you need an opinion on SIFT, go ask your librarian, not me. SIFT is past its teenage years; it’s gone through college, gotten married, and is starting a family of its own.

So why was I focusing on a solved problem, especially when people seemed quite interested in my take on the new? Mick Jagger performs “Sympathy For the Devil” because he has to make his nut, I was doing it by choice.

On the flight home I relented, like St. Paul on the Road to Damascus with less leg room. I would quit dabbling with AI on the margins and throw myself fully into how AI intersected with critical thinking, argumentation, contextualization and source verification. And if it turned out it sucked I’d get myself on that circuit explaining exactly why it was an unredeemable suckfest. If turned out to be amazing then that would be great for society, but a sign for me to find somewhere else I might be needed. If it turned out to be somewhere in-between — if there turned out to be some insight I had into how to make it more useful — then maybe the excitement that had left me would be rekindled with the new project.

Luckily, it turned out to be the in-between.

What people meant when they said “SIFT for AI”

I won’t narrate my whole AI journey. In the beginning I just focused on getting very very good at using AI to contextualize and evaluate claims. I built prompts that broke down arguments into Toulmin diagrams. I tried to prompt it to model discipline-based reasoning accurately. I built Deep Background, a prompt thousands of words long that is still one of the best fact-checking prompts out there (even if it does blow through all the reasoning tokens you get on the free versions in about two minutes). I tried little experiments like using an LLM to fact-check 50 claims in the MAHA report over the course of a long weekend. It worked, though I do not recommend it as a weekend activity and would suggest that even on a weekday it will mess with your mental health.

For a while this work was so interesting I kind of just forgot about the “SIFT for AI” thing altogether. But I came back to that question over the summer, mostly prompted by three separate situations where people inquired about refreshing or rebuilding old SIFT materials. And for each of those, the question came up — “What does SIFT for AI look like?”

If I was going to refresh these materials I needed an answer.

And luckily, I finally understood the question. People weren’t asking for a replacement for SIFT. They were asking for something that did for AI literacy what SIFT did for information literacy.

The Doing before the Thinking

What were they actually asking for? What gave people such warm fuzzies about SIFT in the first place?

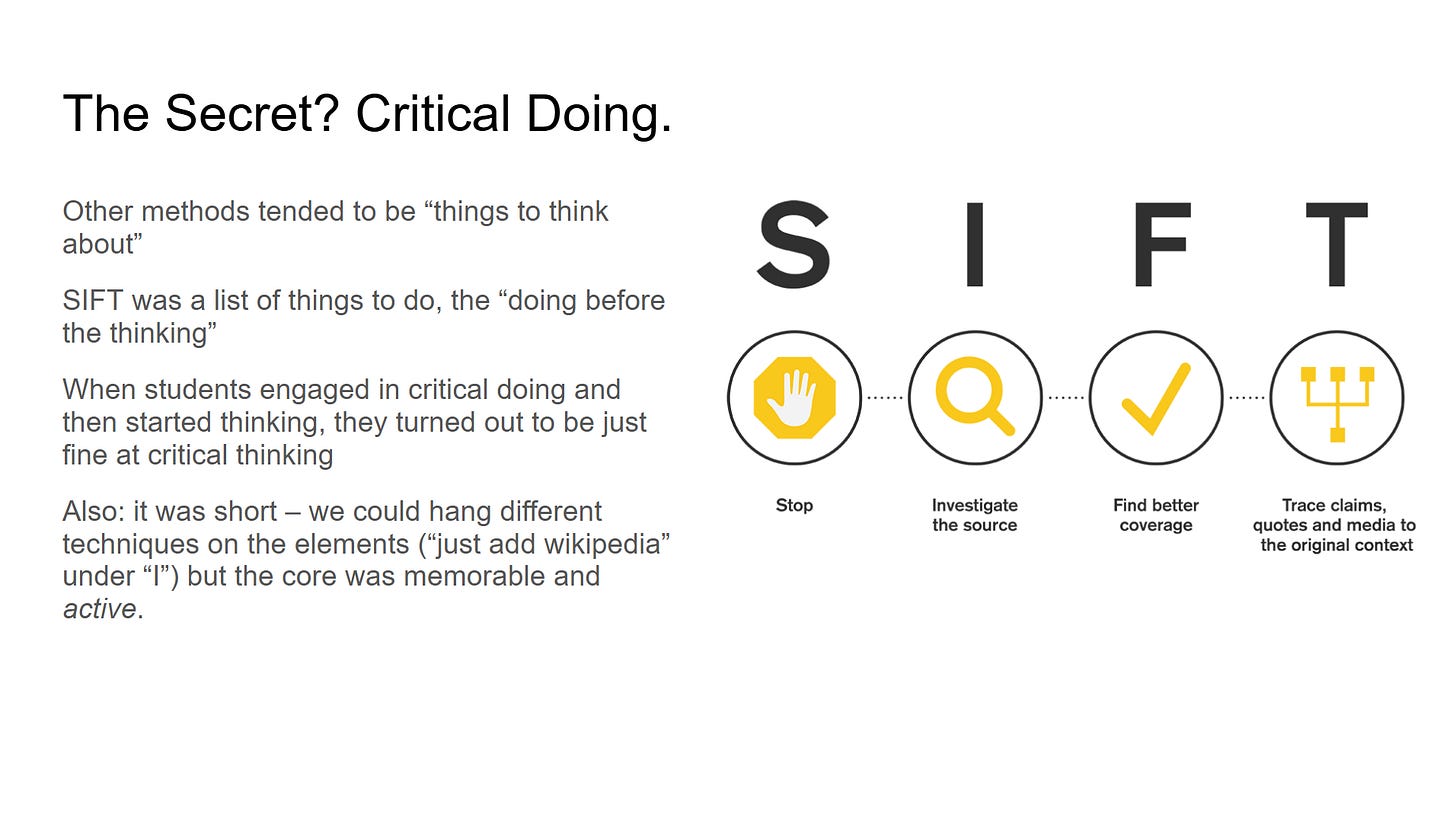

What people liked about SIFT, and how it changed the approach to information literacy… first and foremost, it was its focus on critical doing.

SIFT entered an incredibly crowded instructional market in 2017, as platforms, centers, hundreds of others were all releasing advice and dozens of acronyms to the public on how to navigate a flood of misinformation and spin online.

But with the exception of SIFT and lateral reading, the solutions offered tended to be one of two things.

The first type of solution was bags of personal tips that might work sometimes and not work other times. Often this took the form of a reporter just saying what they did and assuming that what they did was a) good advice, and b) something useful for other people. These weren’t always horrible, but half the time they were more folk wisdom that tested methods. You’d get this sort of thing, the “Well, what I do is I look at the reporter’s name on an article, then I review their other articles to see what their publication history and bias is”.

The problem with this was a) no, you don’t, and b) no, no one else will do that either.

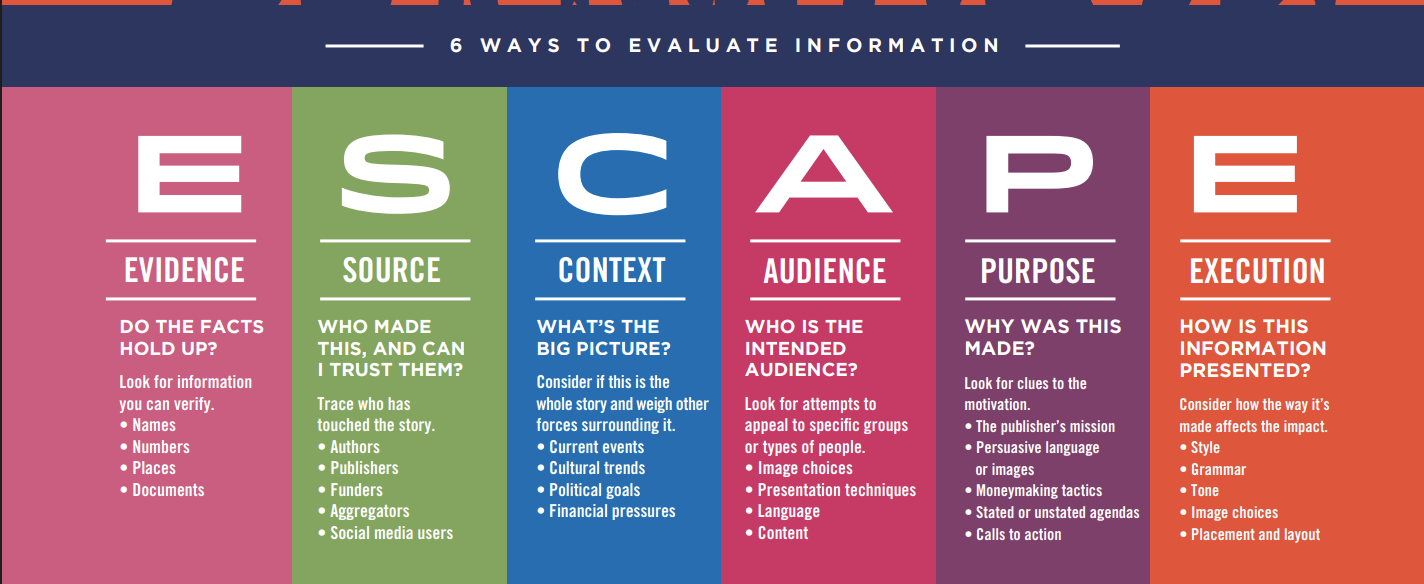

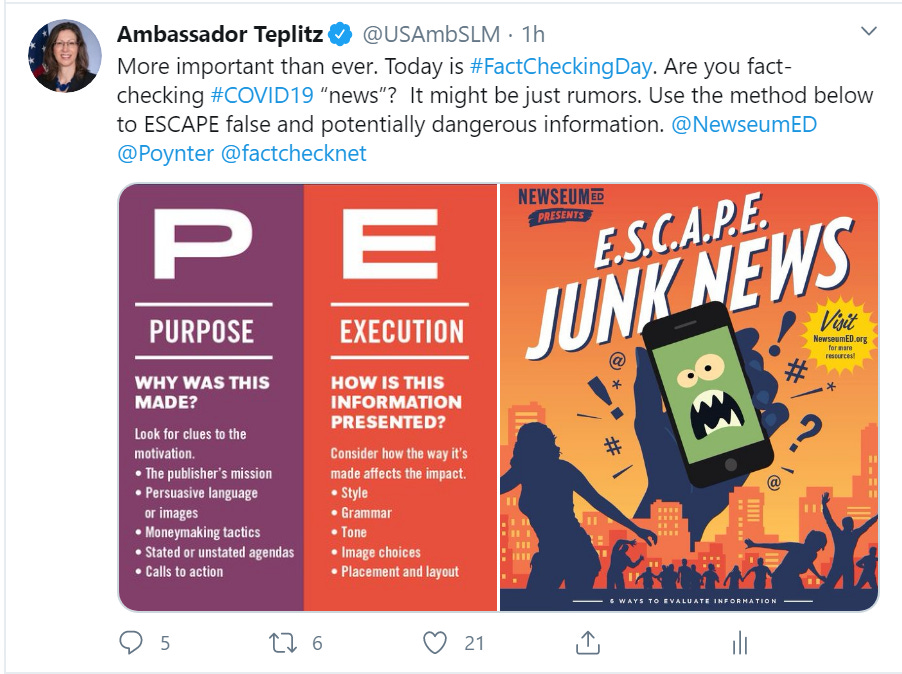

The second sort of thing, which I unimaginatively call dozens of things to think about, often had a lot of money behind it, and was usually produced by a platform or foundation sitting down a bunch of academics and coming up with lists of questions to ask oneself or “things to look for”. While inspired by earlier work like the CRAAP checklist, I think the height of this trend was the Facebook sponsored, Newseum-endorsed “E.S.C.A.P.E. Junk News”, complete with six letters all with four to five questions and “things to look for” under each.

Lists of questions aren’t bad, and I agree all of this could be useful as an in-class exercise to learn about differences between genres of publication. But it was the height of ridiculousness to tell students this was an effective way to figure out whether they were looking at a non-partisan national publication, a respected but biased think tank, or a backward partisan rag.

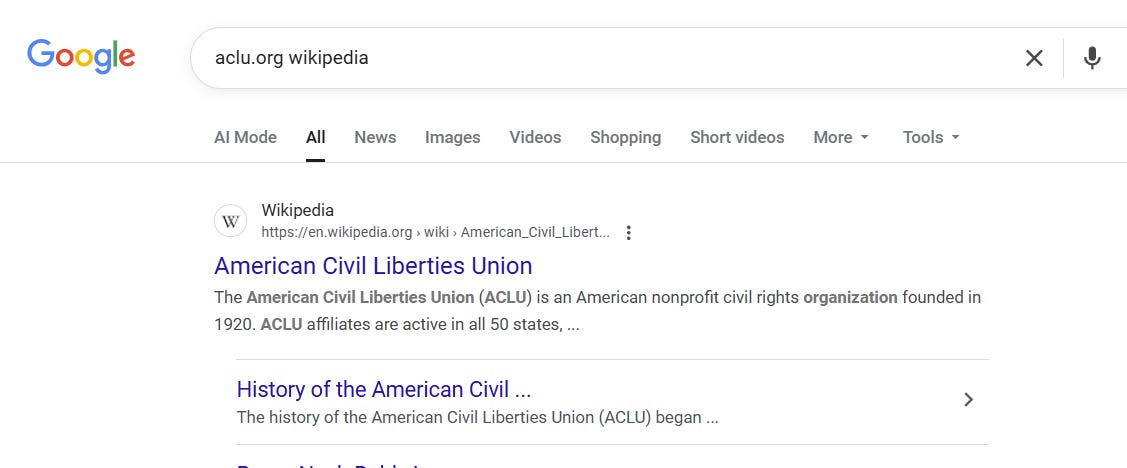

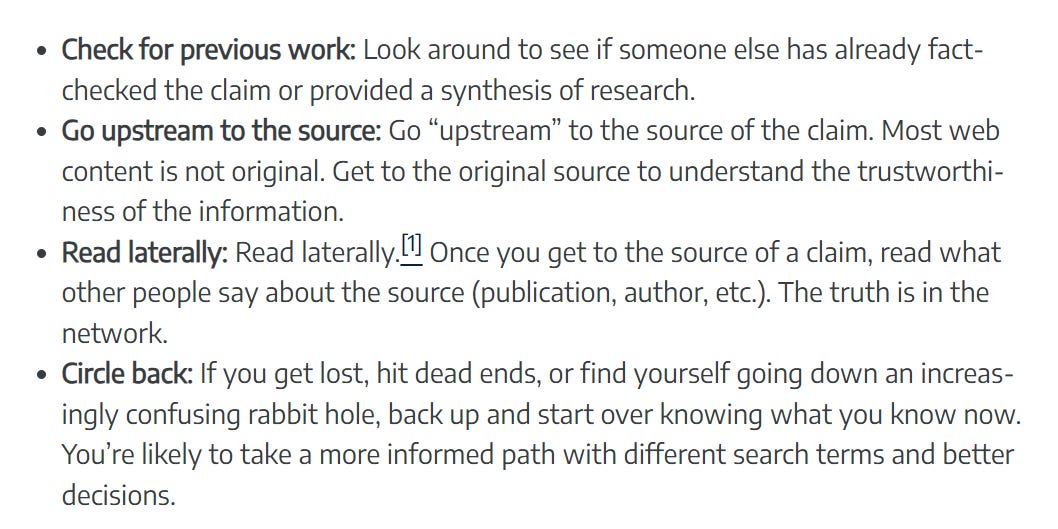

The primary lateral reading approach to telling if the publication you were looking at was a national publication? Use the web to check the web: look it up in Wikipedia.

That wasn’t always the end of it, of course. You’d have to know some basics, like the fact the the partisan lean of the editorial page, as described on Wikipedia, was not necessarily a description of a reporting lean. And if Wikipedia pointed out that research site you were looking at was from a lobbyist operation, sure, you’d have to know what the word “lobbyist” meant.1 But assuming you got yourself to the Wikipedia page repeatedly, you would eventually learn stuff like that, which is why so many SIFT students ended up with a broad knowledge of the media landscape even though we never taught them that explicitly.

Underneath it all was our realization: the secret to knowing things is doing things. Thinking is important, but it rewards those who engage in the “doing before the thinking” — taking steps to figure out where the thing they are looking at came from, seeing what others know about the event or claim.

SIFT combined three things, all focused on the doing.

First, the techniques I suggested were not simply opinion. I would take a technique like Just Add Wikipedia and run it against hundreds of different examples to see how it performed. I would reduce its complexity over time — going from telling people to go to Wikipedia and search it to telling them to search Google for the relevant URL or organization name followed by a “bare keyword” approach, for example aclu.org wikipedia.

When looking through a method, if I could shave off a step, I’d shave off a step, and if we could make the execution more broadly applicable I’d make it more broadly applicable.

Second, I took those sets of honed techniques and we put them in an action framework that focused not on seven or ten categories of things to think about, but the most important categories of things to do. Those categories came out of a lot of reading, partially out of some research from what is now the Digital Inquiry Group, but also just a sense over time that they were they had the right mix of abstraction and concreteness.

Influenced by early findings of Wineburg and McGrew, I got lucky, and locked into a decent set of categories pretty early:

By 2019, I’d gotten to the final form, which ditched the “circle back” as something people just weren’t getting,2 put the the “habit” of STOP into its own move, and formulated the the rest of the categories much more cleanly, based on dozens (maybe already hundreds at that point?) of workshops and class sessions, and informed by application to thousands of claims, photos, and quotes.

And that’s how we ended up with that structure. Well thought-out paths of action combined with broadly and relentlessly tested techniques. So by the time it reached most people it just worked.

The final piece was a pedagogy, developed through videos, blog posts, and workshops. And here too the critical doing elements were central.

The tendency of some information literacy sessions at the time was to either have a lot of course-like material (“What are the eight indicators of newspaper quality and how do they relate to the history of yellow journalism?”) or to have students look at something and reflect.

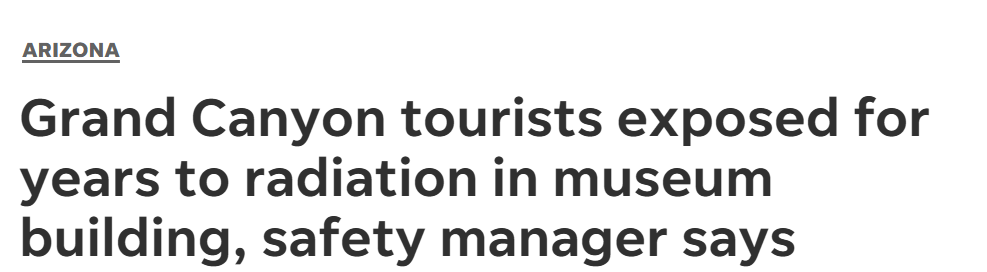

SIFT lessons were an active, information-foraging journey. You’d start with something like this:

And then have some of the class investigate the source, some find better coverage (which in this case could mean more recent reporting). Then you’d go out and ask what people found:

Where’s it from?

“azcentral”

Any info on that? Someone else?

“It’s a USA Today site.”

What’s “USA Today?” Ideas? John?

“Seems like a well-known newspaper? Old — 1982 — and lots of subscribers”

You’re killing me that 1982 is old. Anyone else? Where’d you all find that information?

“Wikipedia”

What did the azcentral article say?

[Multiple answers]

Anybody find some other coverage on the event? More recent stuff? What did that say? Where’d you find it? What do we know about that source?

[Multiple answers]

So what do we think of this? (and so on…)

In short —

Introduce example

Have class go out and information forage

Bring back information to class on source, other coverage, original context, and say how you found it

Synthesize this information in either group or full classroom discussion and think about how it shifted our initial perceptions (if at all).

It wasn’t only a class of “doing” — it was a class where students watched other students doing. Where the doing happened before the thinking and propelled the thinking forward. A lot of classes work like this of course, but this simple artifact => information-foraging => sharing & expansion => synthesis really worked for this stuff and created an active and fun environment that wasn’t about knowing the answers but finding them and thinking about how they shifted our perspective.

Those were the three legs of the stool: smart categories of moves, battle-tested and refined sets of techniques, and an active, energetic pedagogy that rewarded good information-foraging and synthesis rather than knowing the answers already.

In that configuration what I kept hearing from many educators was that it was the closest thing to magic they had ever seen in a classroom.3

AI Literacy as “Critical Thinking with AI”

Which brings me back to this question of “SIFT for AI”.

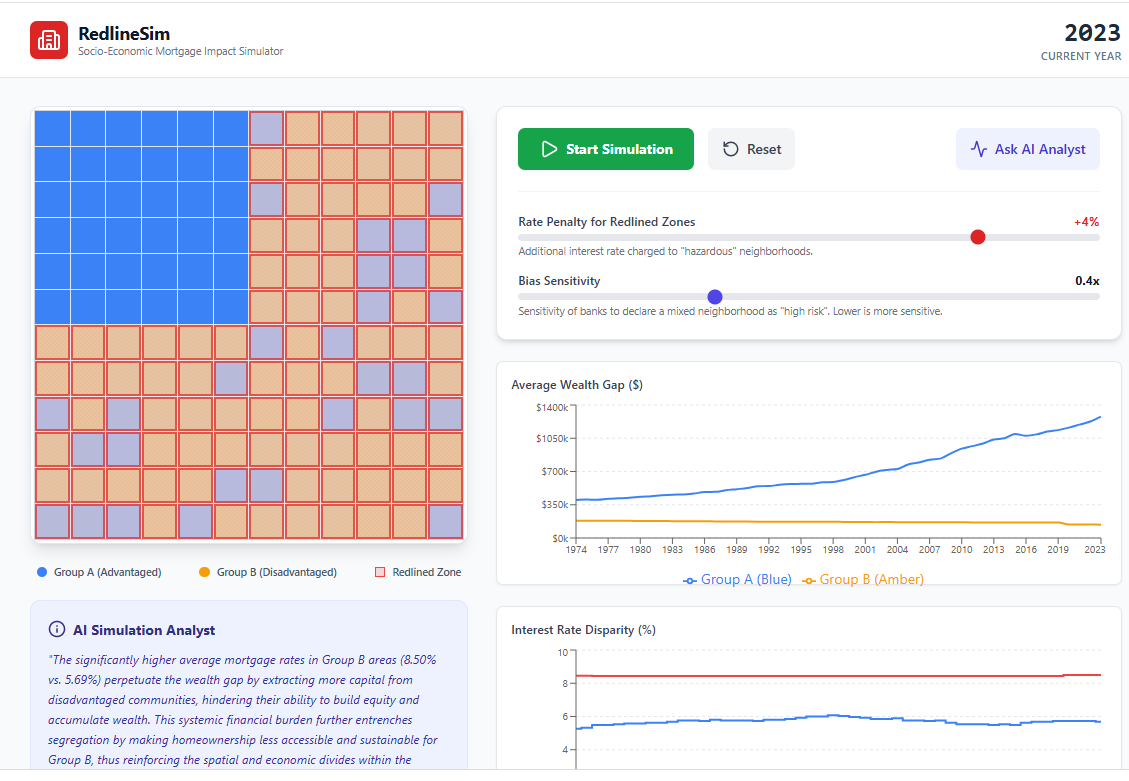

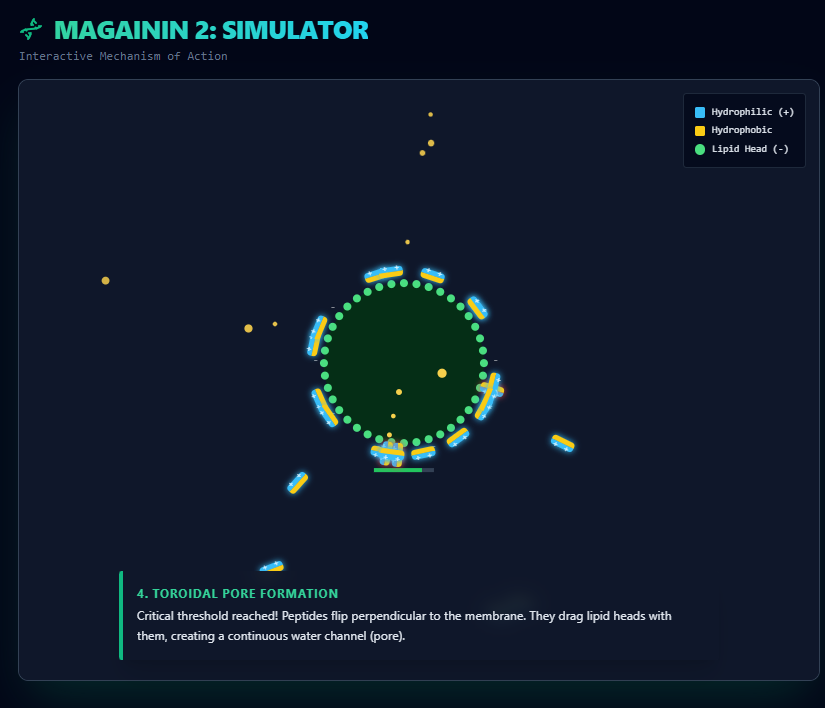

First, let me say that in the realm of AI and learning there is a lot more than just information-seeking and synthesis. Just a couple days ago I was playing around with the ability of Gemini 3 to build quick simulations in as little as 20 minutes that showed how redlining worked:

Or how certain peptides have antimicrobial properties:

I think there is a whole host of opportunities around both instructor and student building, around knowledge rehearsal and retention, around direct explanation of difficult concepts, getting feedback on work and the like.

But if we narrow our focus to elements of AI literacy around disciplinary thinking and information-seeking4 I think what the SIFT people are asking for is something that does for AI use what SIFT did for search literacy, across all three of those legs of the stool: moves, techniques, pedagogy.

There’s a lot of good work in this space, and I’m well-aware that while I was in my “SIFT for AI is SIFT” curmudgeon phase a couple years ago many people were already doing the hard work of thinking how this intersects with information-seeking and in-class pedagogy. So if you’ve been in the space since 2022, you’re absolutely welcome to ask “Who brought Mr. SIFT to the party?” I get it.

I don’t claim originality here. I can only speak to a need I see that is still unfilled enough that people still ask me the question “What does SIFT for AI look like?” Which is to say, what do fans of SIFT want out of AI instructional approaches?

But SIFT is ubiquitous and has lots of fans. It’s a question worth answering.

Chocolate Memory

For me, the answer to the question is exemplified by the Chocolate Memory task I ran at Simmons and Trinity last week, one that seems to have greatly impressed a lot of people in those two rooms and some folks who watched online as well.5

Chocolate Memory starts like a SIFT task. In some ways it is a SIFT task. We take a very simple starting point — does this research show what people think it shows?

I say SIFT task, but it honestly is the same structure as so many class tasks in undergraduate education. You take something that is initially simple, and then bit by bit you guide the students in peeling back the layers of the onion. You do this in sociology, quantitative reasoning classes, physics. Everything, really. It’s a core instructional design pattern. Different disciplines peel back those layers differently, but the point of a lot of what we do in undergraduate is to show students the variety of ways you can explore an issue like this.

So we have this task, and the naive take on this story is “you eat chocolate, you remember things better.” We decide to throw it into the analysis machine for deeper analysis. We get it up on our AI “workbench” and take a look.

For the sake of streamlining the instruction I have the participants click a link to get an initial response. This skips our “Get it in” step because we’re going to focus on the “track it down” and “follow up” steps.

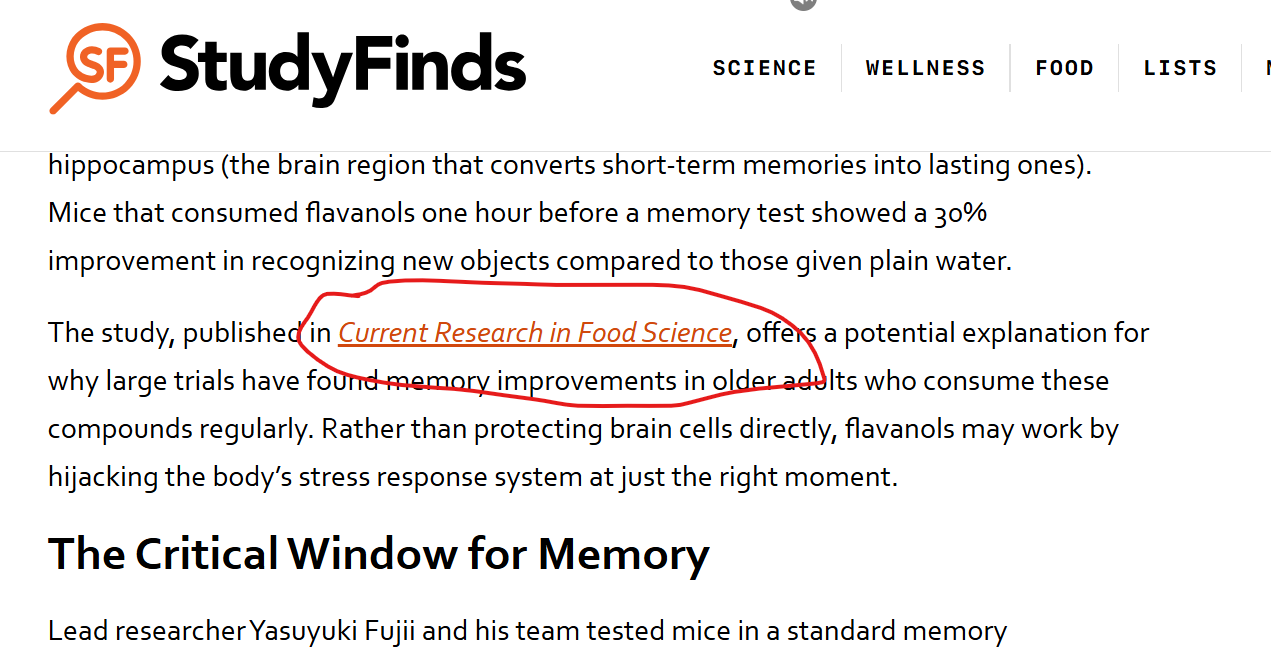

In this case, we do stop the students and have them track it down, jumping to the Study Finds link on the side which then links to the original article. We don’t have them read the first response, because we’re going to shape it with a follow-up in a minute.6

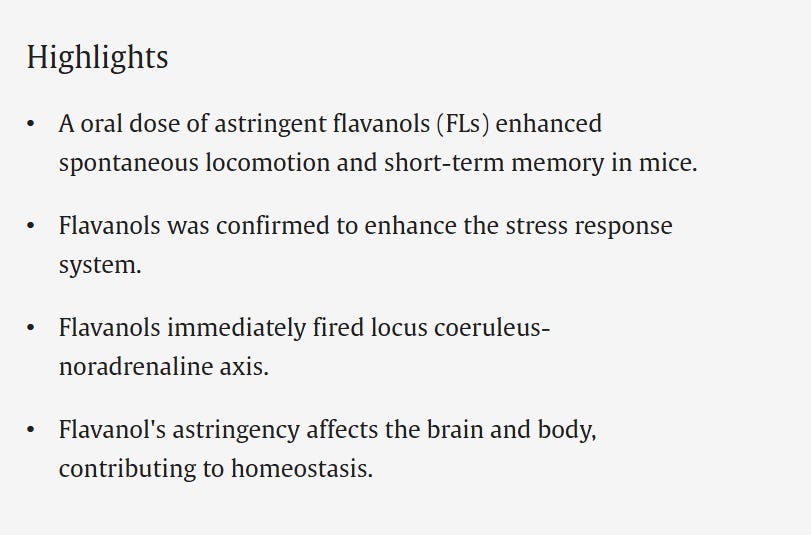

The participants use the features of the platform (or a crafted follow-up) to surface the original report. For various reasons, that’s often two hops, from here:

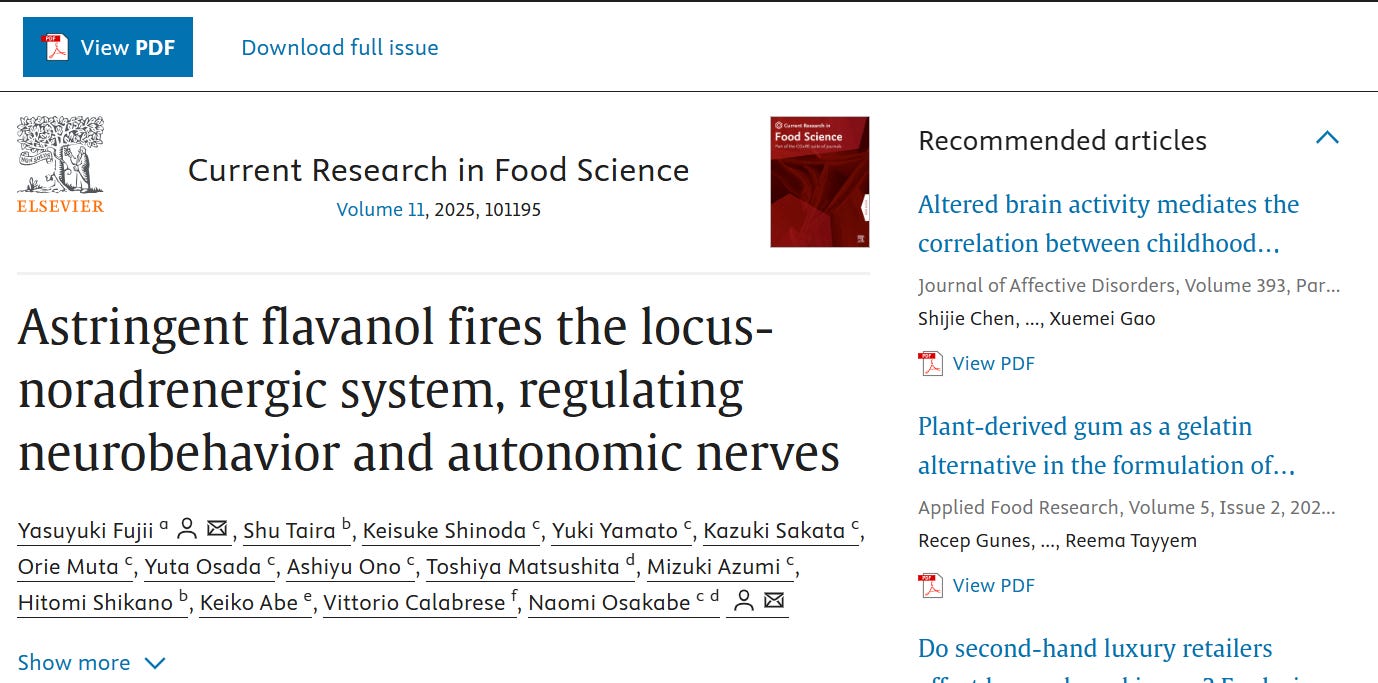

To here:

We’ll note for the participants that this is a pretty common pattern for links to papers AI Mode and other LLMs — very often they won’t initially serve up a direct link, but instead a page that links to the study. You can either coax it to return direct links through a follow-up or dig a couple links down.

As a teacher we might then ask the students a couple simple questions:

is the article recent, or is this old news (it’s recent)

is it a preprint or in a journal (it’s in a journal)

do the article highlights mention chocolate (they don’t, they mention flavanols)

Great. That’s a little “track it down” activity to get the class primed, and to remind them they always want to eventually ground claims outside the LLM.

Wrestling with evidence

Now we serve the main course. (Of this exercise at least).

The students copy this text:

Evaluate the evidence for the claim that _____ and provide a table that matches evidence to rebuttals and rates the strength of the evidence

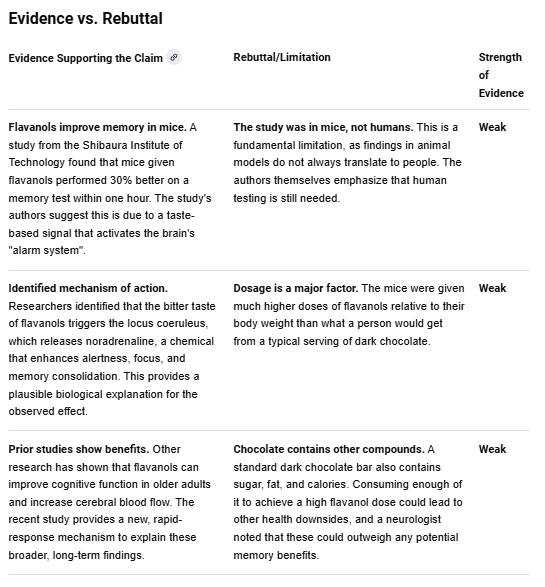

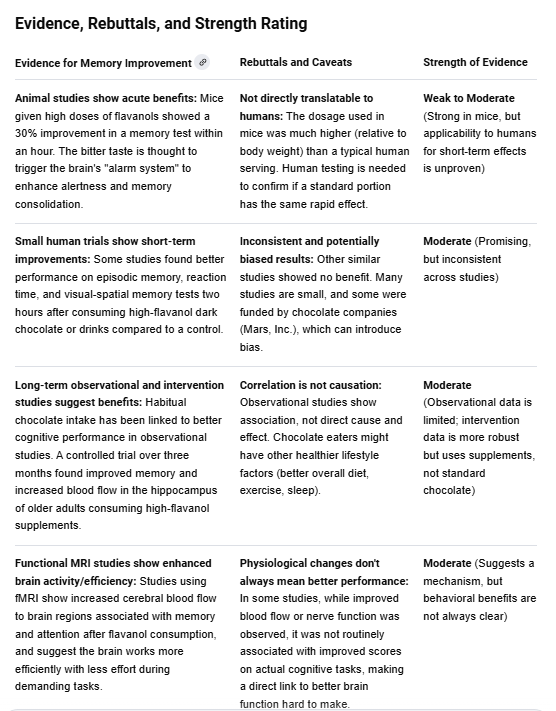

And they think about what they are going to fill in that blank. What is the claim?

It could be narrow —

Evaluate the evidence for the claim that this study shows chocolate increases recall and provide a table that matches evidence to rebuttals and rates the strength of the evidence

It could be a bit broader:

Evaluate the evidence for the claim that eating chocolate improves memory and provide a table that matches evidence to rebuttals and rates the strength of the evidence

Just the process of formulating claims can be difficult for students, so filling in this blank is part of the learning activity. They each plug in the text and run it. (We had most people do it on their phones, which worked wonderfully).

and another…

Then we have them do a bit of think-pair-share. We have the students take what they have found in their response and talk to one another about the evidence. What evidence do they find compelling? Why? Is there anything that is striking in the results? Anything they want to dig into more?

For example, in the above result row one says “the bitter taste” of a flavanol dose was seen as possibly stimulating some of the effects — is that a correct summary? And if so, does that mean once the chocolate is sweetened with sugar it would lose its impact? On the other hand, there does appear to be a long term study mentioned in older adults that had impact consuming supplements — that seems to warrant more investigation. Although again, it’s supplements, not chocolate.

There’s lots to talk about here, and a lot of it is a mini “research methods for the general public” class. You’re discussing with your class partners or class group what the strength of mice studies relative to fMRI studies are, and how these things might or might not combine together to paint a fuller picture. You don’t fully know what you’re talking about, these observational vs. intervention studies and so forth, but you’re starting as a student to get a fuzzy sense, to build some questions.

And of course a good teacher can take that forward momentum and use it to steer the conversation towards important concepts and topics.

Giving students the map — then letting them explore

In the above case we’re doing things with research and study design, but of course you can develop such activities around historical thinking, sociology, urban planning, education — any place where people apply disciplinary lenses to real-life problems, and in particular anywhere where students have to evaluate the strength of arguments and evidence.

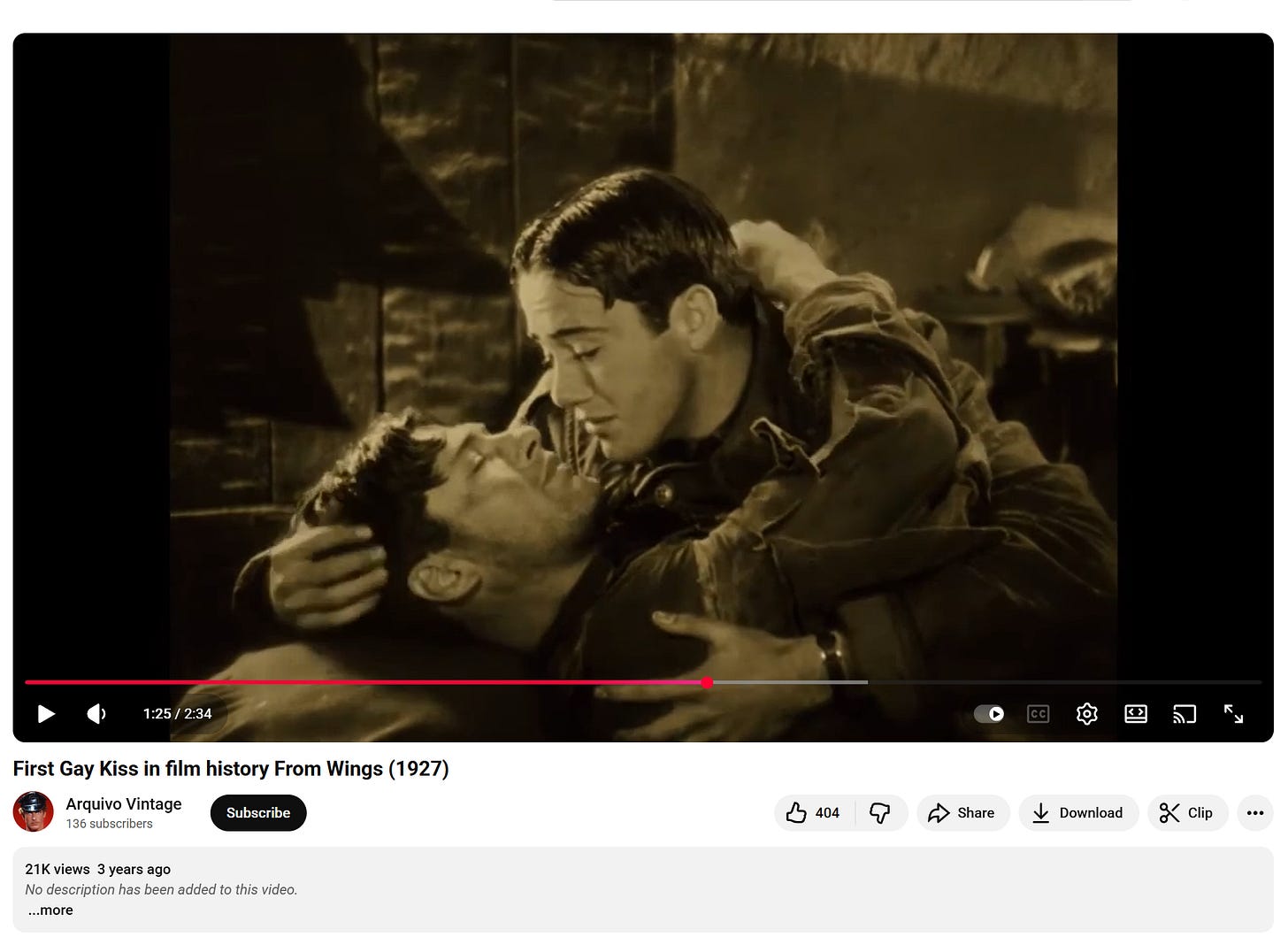

As an example, a recent activity I have been working on involves something often referred to as the “first gay kiss” in mainstream cinema, from the 1927 film Wings. It’s an interesting task, because to the modern eye this is scene seems quite clearly a gay love scene:

When you put that into AI Mode using Gemini 3, though and ask it to read that scene like a historian, you get a set of other quite interesting lenses:

There’s the fact this happens in a deathbed scene, and the trope of the “deathbed exemption” where characters are allowed to express emotions at a level that are generally frowned on in day-to-day life. There is the WWI-bound concept of “trench intimacy” — that the closeness of soldiers in this way was a necessary protection from the psychological horrors of war. And there’s just the fact that in silent films all expression had to be over the top. This was not a subtle visual medium!

Students can then research each of these ideas more and talk about the way it changes their view of the film. There’s also another lens around the answer surfaces about what the film may have meant to certain audiences apart from intent.

The students can share these various concepts and talk about what evidence supports these various interpretations. Can they remember other “deathbed exemption” scenes in other films? Are there papers that describe the “trench intimacy” concept further? Are there modern examples of subcommunities “adopting” film scenes as their own, even where the narrative ran against that reading? How much does intent matter, when audiences even at the time might have been desperate for any representation at all?

Cognitive offloading, or disciplinary scaffolding?

I think a possible reaction to this is that the students are not thinking at all. After all, isn’t it the LLM that is coming up with these alternative interpretations and these charts of evidence? Seems lazy, right?

But I think this gets it backwards. There is no way that any student without significant knowledge is going to be able to surface these possibilities. The ability to look at a snippet of film like this and surface three or four perfect lenses on it, or to look at a research paper on chocolate and surface the six most important questions about the methods-findings fit is a level of expertise that people gain only after years of experience.

But once these things are surfaced students are capable of engaging in verification, evaluation, synthesis and exploration. And exposed to that over time with guidance and a decent set of educational materials, students will start to build the foundational knowledge, skills, and understandings to do it on their own.

What is happening here is not that AI is doing the thinking for students — rather, with prompts like these AI is generating preliminary maps of the information landscape. Students are then using those maps to navigate that landscape, and hopefully developing familiarity with the subject and patterns of critical reasoning (both general and grounded in the discipline) as they go while also developing helpful knowledge around how LLM tools work and how to use them effectively.

In some ways this isn’t so novel. One of the first classes I got to integrate SIFT into at Washington State (way back in 2017) was Tracy Tachiera’s class on family studies and we also developed activities for classes on climate change, American politics, and statistical reasoning.

Our pedagogy with AI — start with a simple example, have students information forage, bring back the findings and synthesize — is very similar. But what I’ve found so far with LLM use is that the possibilities for disciplinary intersection are radically expanded.

With SIFT, finding examples that fit the goals of a class could be laborious and time consuming. You had to identify examples that were interesting, targeted on core understandings, but where the information environment wasn’t too overwhelming for students to navigate. Since context would be needed to analyze the claims introduced, a lot of times there’d be a bunch of “table-setting” required to set up the example. Very often you’d choose examples that tended to have very clear outcomes because handling too much nuance in the space of the activity’s time frame could be challenging.

My experience so far with AI has been different. As I think I demonstrated last week at Trinity and Simmons (or rather as we demonstrated — thanks to all the participants!) LLMs make it easy to spin up a meaningful contextualization exercises that provide entry points into topics like research design, or anything else you’d like to tackle, using that same zippy SIFT-like approach with cycles of classroom synthesis and information foraging.

Next Post: Useful Moves and Battle-Tested Techniques

In my next post, I’ll talk about the other two legs of the stool: broadly useful moves and battle-tested techniques, and how the “get it in, track it down, follow up” framework provides a structure that pushes students to do the simple things that make their information-seeking sessions more productive, enlightening, and maybe even enjoyable?

Hopefully have it up by Sunday!

There were always a segment of students that were somewhat resistant to improvement by SIFT, and one of the biggest correlation we found wasn’t anything around beliefs or traditional measures of media literacy — it was basic reading comprehension, which was a tough nut to crack.

“Circle back” partially came out of the original lateral reading paper where it was identified as a behavior that fact-checkers engaged in. It’s important, but for whatever reason people found it confusing in the core set of things to do. Instead we taught some of those habits under the other categories — how to read a SERP when looking for better coverage, and how to know you need a better search.

This sounds like an exaggeration — it’s not. Among others, you can ask no less than Bonni Stachowiak.

Vs. things like building software, producing reports, or planning vacations…

This might seem arrogant, but the truth is I got many comments from participants on the scale of “How do we put this thing in every general education class?” from faculty, especially in the second run at Trinity.

We’re going to follow the principle here of “throw the first response away.” This is a difficult thing for most people to understand about LLMs — you just generated a response and you’re not even going to read it? But the point of the first answer is for the LLM to get grounded in the topic and the issues around it, the next moves are where we do your thing. If you get exactly what you need there on a glance or see a source you want to jump to, have at it! But really you’re just booting the system up.