When wrong LLM answers get you to the right information

"Why do you say that?" can be just as instructive with an LLM as it is in real conversation. Also: I make you learn Stalnaker.

Mostly when I read more heated debates for and against LLMs I am struck by the fact that people don’t seem to know how their own human-to-human conversations work. For a while this made me frustrated. More recently I’ve seen it as an opportunity. After all how often do you get to talk about formal pragmatics on a blog post? (Or more specifically a blog post that someone might read).1

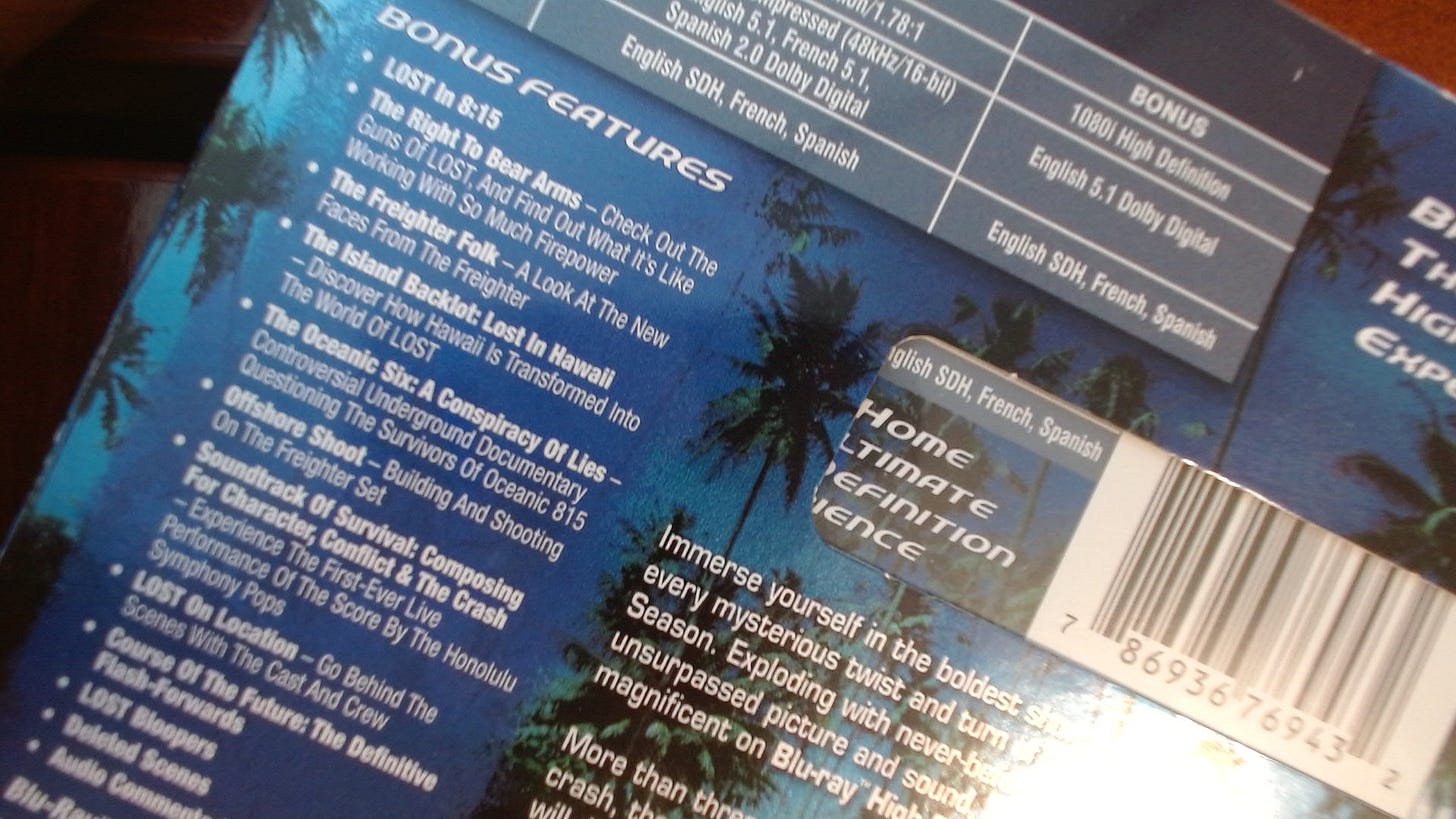

Take this small exchange with Google’s AI Mode. I am interested in buying a Blu-ray player. Why? Because look at what we lost here folks! Look at the beauty of this, look at these extras! We have to go back, Kate!2

Anyway, there’s a store near here called Video Only which sells recent tech but also some older tech and puts out old-looking ads. And there’s an ad for an upscaling LG Blu-ray player this week:

It starts out by giving me some useful information:

Looking at this I visually verify that it’s likely (though not certain) to be the center item here, which means despite the price drop it’s probably overpriced. Maybe I’m wrong about that, but it’s a good question to walk into the store with.

However, it also says something later on in the response, which is confidently wrong. It says that this offer I pasted in is clearly from an older advertisement.

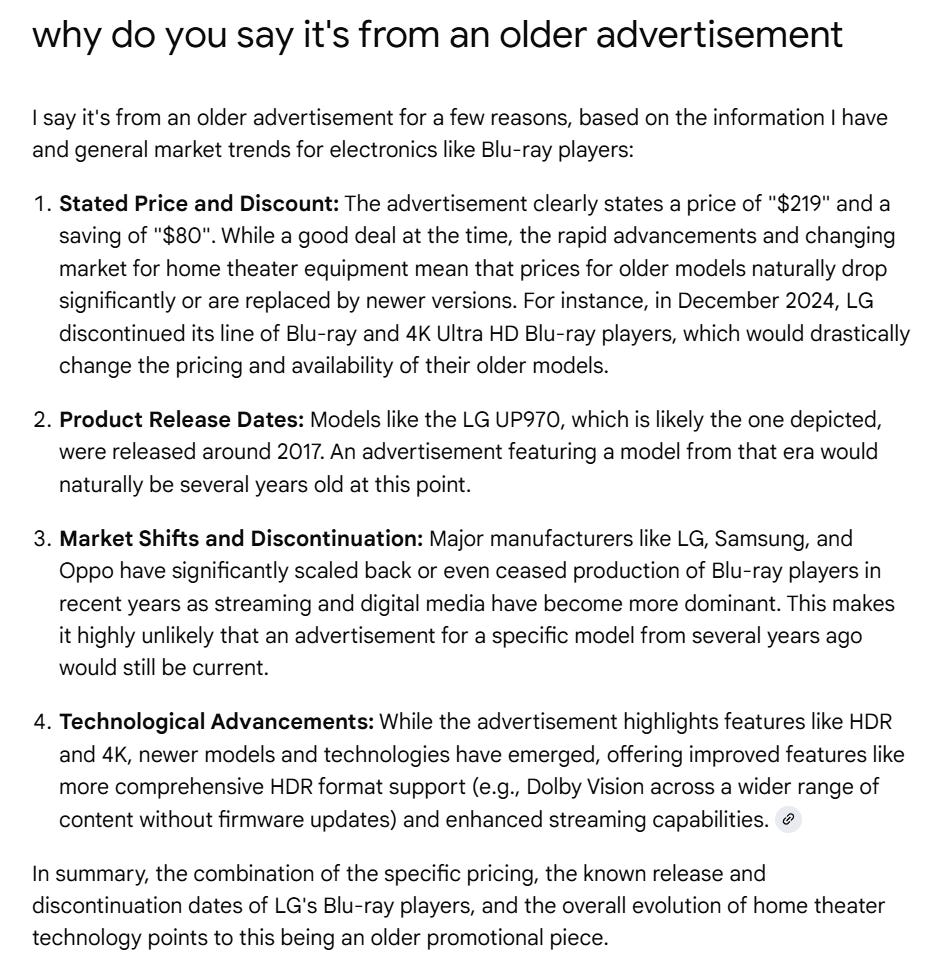

This is the sort of answer we often mock with LLMs, because people think the point of dialogic systems is to give you perfectly correct answers. But I decide to push on this. I have a light evidence prompting frame of “why do you say” that I apply here: “why do you say it’s from an older advertisement?” The response it gives me is completely wrong in the sense that I know that what it is arguing for is as false as a claim as saying that the moon is made of green cheese. But it’s also incredibly valuable feedback! It’s a treasure trove of things that are important to this process I’m engaged in that I didn’t know:

I learn, for example:

this model (and all LG models) are discontinued as of 2024

this model came out in 2017, it’s eight years old

This model (and other older models) might not support newer features of my TV like Dolby Vision (which is super important to me!)

Of course, you can say none of this is actually why it said what it said. But that’s a bit beside the point. In being forced to defend the position it surfaced valuable information for me.

Stalnaker and dialogue as Common Ground Game

How do we look at this? One way is through the lens of discourse pragmatics.

Back in the early 1970s Robert Stalnaker gave us one of the most useful models in pragmatics: his model of the common ground.3

What he said was roughly this. When you say to me that Heloise just walked into Vivace in Capitol Hill, you’re proposing we agree that we both mentally inhabit a world where that just happened, and that any future conversation can take that as common ground to build on.

You want to get on to the discussion of what Heloise in Vivace means, but first you have to submit to me that it happened (and I have to accept that) before we can go there.

Now I might just accept that and say “Really? Tell me more!” And they you would proceed submitting more stuff into the common ground. Is she living in Capitol Hill now? Just visiting?

But I might also say, are you sure? Vivace isn’t even open yet!

You come back and say: “Actually that’s true on weekends; but on weekdays they open at 6:30 a.m. for the business crowd.”

As we go back and forth in this wonderful way we are establishing the common ground, the set of propositions that we can both take for granted in the ensuing conversation. What Stalnaker got at was that conversation is a sort of game where we build the common ground together, in alternate turns where something is proposed to be adopted into the common ground, then either accepted or rejected:

You try to add the fact that Heloise walked into Vivace just now into the common ground.

I reject the addition. In my rejection of the addition to the common ground I try to add my own addition to the common ground — Vivace isn’t open at 6:30 a.m.

I fail too! You partially reject my addition: Vivace does open later on the weekend, but on weekdays it is open at 6:30 a.m.

I accept that addition to the common ground.

You then resubmit (implicitly) to the common ground Heloise just walked into Vivace.

I ask how you would know that. You submit to the common ground that Lucia just texted you and said so.

I accept into the common ground that Lucia is at Vivace and texted you, and that she did relay this, but question her ability to recognize Heloise, who she hasn’t seen for ten years.

You reject my addition, noting that Heloise saw her at that party three years ago…

And so on.

Here’s what’s beautiful about this, and why I’m obsessed . In trying to submit a simple thing into the common ground we can end up discovering a lot of stuff we didn’t know. At the end of the conversation I learn something about Heloise, but I also know the working hours of Vivace, that Lucia goes to Vivace sometimes, and I’ve refreshed my memory about that party three years ago. Conversation is so often a process of realizing we live in different worlds in terms of what is known to be true and what isn’t, and working to reconcile those differences enough to where moving forward is possible at all.

Wrong answers are useful if you ask for a defense of them

This is a lot of theory about a Blu-ray player. But the point I would make is that much of conversation — and in fact research itself — works like this. Someone makes a point we disagree with or are not sure of. We read their reasoning, and in the process we adopt a lot of smaller beliefs even if we reject the at-issue proposition. As we understand the defense of the position we come to more detailed knowledge about the world that is in some ways a by-product of the conversation but in other ways the whole point of it.

I am sure someone on the internet will say “Cool defense of wrong answers, bro” or something like that.4 And of course I’d rather have right information from the start than wrong information.

But my point is even if it turns out that Lucia was absolutely mistaken about it being Heloise in the coffeeshop, that doesn’t mean that conversation was a waste. You can learn whole histories in the process of debating whether a single event happened. Likewise if you see interactions with an LLM as a back and forth, and look (with a skeptical eye) at the response from the LLM as a submission into the common ground, you can learn a lot from a wrong answer there as well. But you have to push back for evidence, and you have to be on the lookout for smaller useful propositions even if the larger proposition is undeniably wrong.

This was the insight of Stalnaker. Conversation is sort of like a game. The point may seem to be the headline proposition — a question of coffeeshop presence or a debate over the vintage of an advertisement — just as the point of soccer is to get the ball in the net. But the work of conversation is building the common ground, and through that expanding our shared knowledge of the world. And that happens whether the ball goes in the net or not.

In this case, a follow-up on a wrong answer to my initial query led me to realize that I should be looking for players with Dolby Vision support, and that the player advertised does not seem to provide that. That wasn’t the point of the query, but that was the value of the exchange, and prevented me from making a pretty substantial error. Understanding this pattern a bit better might help us form better ideas on how this technology might be useful.

I’m making a bold prediction here that people won’t ditch this when they reach the formal pragmatics part.

I stole this LOST joke from a reply to me posting this picture on Blu-sky. There may also be a “Not Penny’s Boat” joke to be made but I will not joke about that scene, I am not a monster.

The full idea involves something called possible worlds, and an earlier draft of this tried to explain the model at that depth. But I came to the conclusion I can explain it without them. Possible world theory in linguistics is hard for people to grasp, so I’m engaging in simplification here.

I used to get mad at these people. Lately, I just feel sorry for them. Eventually, I imagine, I just won’t think of them at all.

Extra heart for footnote 4.

Hadn't thought about a modal logic analysis of LLM truthtropic dialogue. Very appealing conceptual space.